| | NEWS

Shomer Tziyon Hane'emon:

The Hundred and Twenty Fifth Yahrtzeit of the Oruch Le'ner

By Moshe Musman

Part Three: The Issues He Faced

For Part II of this series click here.

Introduction

The Oruch Le'ner's recognition as the foremost halachic authority in Germany brought many contemporary issues to his attention. He and other German rabbinical leaders were faced with the dual responsibility of guarding and guiding German Orthodoxy during the decades that saw the insidious growth of reform from an informal circle of Jews who had fallen under the spell of European culture, to a full-fledged movement that introduced far-reaching changes into a Torah to whose perfection they had been blinded by the dazzle of modern European civilization. They arrogated to themselves an imagined right to effect such changes and inflicted untold damage upon the German communities. The dual responsibility of Torah leadership thus comprised, on the one hand, protesting the spurious reform ideology and the reformers' scandalous actions, and on the other, providing the faithful remnant with halachic guidance for the new times that were being encountered.

The Oruch Le'ner's leadership during these times provides the classic example of a Torah giant's vision and his perception of the present and future needs of the community in the country he lived. His diagnosis of the deeper motivations of the reformers and his response to them, his heartbreak over the spread of the plague to yet faithful Jews and his desire for peace and unity, which did not blind him to the direction in which things were moving, are all apparent from the letters he wrote during the Reform movement's series of departures from Judaism.

Likewise, the preservative measures he adopted to guard Orthodoxy and strike a safe path for it through the challenges of the new times, show the same familiarity with the ills of his age. It is clear that he saw the root of the evil in the abandonment of learning Torah, and the only remedy was thus in the application of the youth to intensive Torah study, as is evident from the far reaching vision evident in the Igeres Hakodesh.

The following selection includes excerpts from teshuvos, letters of protest and appeal, and speeches written by the Oruch Le'ner during the years of his stewardship of the storm tossed boat of German Jewry.

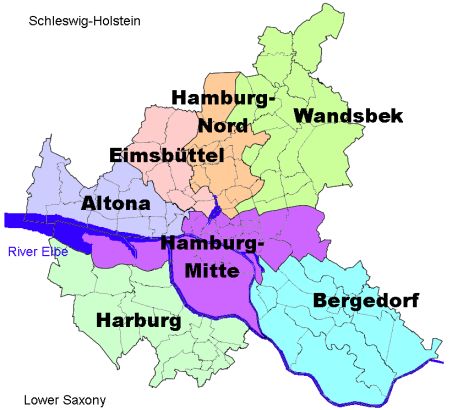

The modern city Hamburg has absorbed its former neighbors and now has a borough Altoona and another one of Wandsbeck

Marshaling the Faithful

In the first half of the nineteenth century reforming ideas spread and took root, with their proponents leading several large communities like the one in Hamburg, all across Germany. Rabbonim like the Oruch Le'ner were well aware of the new desires which nestled in the breasts of many Jews, yet they strove to limit the evil, preventing the majority who had not yet broken with genuine Judaism from doing so by containing them within the kehillos.

It became clear to the reformers that they could not advance their cause by acting in a fragmentary manner, engaging in periodic sparring with the Orthodox rabbonim, over this or that new departure from halacha. They would have to organize themselves some sort of permanent central authority. A reform preacher and journalist, Ludwig Philippson of Magedeburg, successfully appealed for the convening of a national conference.

The most famous of the three Reform `rabbinical conferences' held over the years 5604-6 (1844-6,) was the first, which took place in Braunschweig. It is usually looked upon as the one in which Reform was founded as an official organization with members.

At the Braunschweig Conference, which opened on the twelfth of June, 1844, and lasted for eight days, the foundations were laid for a movement with a mass following, whose motto was to be the remodeling of Judaism, either at the hands of those who wanted to see its radical alteration such as Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim, or of those who wished to preside over its gradual modification, such as Zechariah Fraenkel.

Although the delegates were intellectuals, they were for the most part completely ignorant as far as Judaism was concerned. Mostly young people in their thirties, they had been born and bred in Germany, steeped in gentile culture. Many of them were `preachers' — rabbiners as they were called in German. A number of them held posts in large communities such as Hamburg, Frankfurt and Breslau. Others, like Philippson, owed their fame to their literary accomplishments — it was their works which in fact formed the new Reform Movement's manifesto.

The Braunschweig Conference elicited a storm of protest from the segment of German Jewry that still trembled over Hashem's word. The Oruch Le'ner wrote a letter of protest in which he described the turbulent emotions which overcame both himself and others as they were forced to witness the profanation of all that was holy.

`Over twenty men arose last June and gathered together in the city of Braunschweig, calling themselves `an assembly of rabbis,' despite the fact that many of them are not rabbis at all and can in no way be referred to as such. Even those who are rabbis, are openly associated with the movement for Reform which exists among Jewry. Anyone taking a closer look must be utterly amazed at how a mere handful of men have arisen and presumptuously assumed the title, `The Rabbinical Assembly of Germany.' Many of them do not engage at all in a thorough study of the writings of our rabbis and they defame the Talmud in the very publicity that is afforded their conference.

`Despite the fact that these men have been publicizing their opinions for a long time already, we, the undersigned, would have continued to remain silent, keeping our feelings of bitter regret to ourselves and praying on behalf of our errant brethren. If only this conference would have humbly conceded that its members' acquaintance with our religion is paltry indeed, we would have remained silent. However, the conference's resolutions have been publicized as though their absolute veracity renders them binding.

`With unbridled pride, the key foundations of Judaism have been put on trial without any serious study or research into the sources, and have been declared as completely invalid. The most ancient traditions command not the slightest respect. Neither do the two thousand year old rulings of `The Men Of The Great Assembly,' who numbered among their ranks the last of the prophets.

`The whole purpose is to remove its foundations from beneath Judaism and to negate its entire content, to the point where it will automatically lapse into obsolescence. The wound inflicted upon Jewry by the corruption of our times has been opened already; this move to vilify the holiest elements of Judaism will aggravate it a great deal more... the chasm which already divides Beis Yisroel into two groups will grow much deeper, while this conference is intended to multiply the differences [between the two camps], by sowing hatred and lowering the ethical level of the kehillos, whose sole desire is for their members' unity.

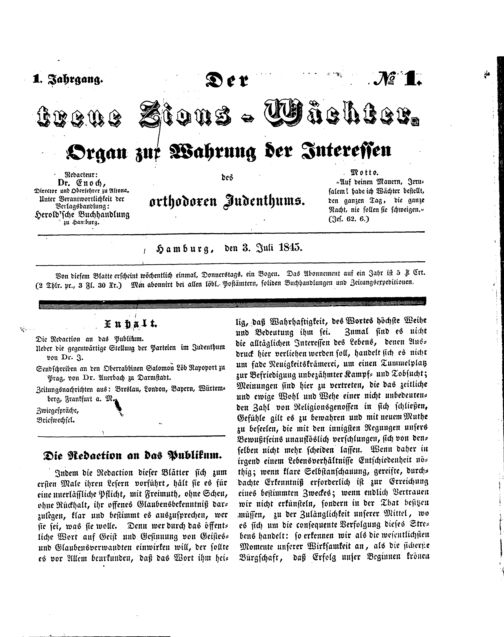

An original edition of Der Treue Zions-Wachter

`However, these men, as well as the innocents who stumble together with them, were mistaken in imagining that they could gain power over Jewry and trample it under their feet, on the assumption that they were a majority. They hope to destroy the Talmud and to establish the throne of Karaism upon its ruins, or more correctly, to enthrone the idol of convenience and the desire for pleasures... however, `Yisroel is not widowed' (Yirmiyohu 51:5)! There are still men who guard over its holy precepts, who are armed with the strong willpower to defend them against all hostile attacks, against wickedness, falsehood and deceit, that are sometimes camouflaged and sometimes open...'

"Seventy-seven rabbonim from Germany, France, Hungary and Switzerland were the first to sign the letter.

"We are certain that an even greater number of rabbonim would have signed this declaration, had they been given the opportunity to do so,' wrote HaRav Ettlinger. `We hope that their signatures will be forthcoming in the future and we are sure that they too, are faithful to our Torah and to their responsibility as shepherds to their flocks, just as we are.'

An engraving of Wurzburg in 1493

Subsequently, the number of signatories rose to one hundred and sixteen. Amongst the better known names are those of the geonim, HaRav Yitzchok Halevi Bamberger, the Wurtzburger rav, HaRav Yisroel Lifschitz, rav of Danzig, HaRav Shimshon Refoel Hirsch, who was then rav of Emden, HaRav Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg, rav of Koenigsburg and the author of the commentary on the Torah, Haksav Vehakabboloh, HaRav Yehuda Assad, who was then rav of Semnitz and later rav of Seredhely and HaRav Moshe Schick, rav of Yergen and later, of Choust.

The letter also bears the signature of HaRav Shmuel Wolf Schreiber, the Ksav Sofer, the rav of Pressburg, who signed together with the members of his beis din. From a letter by HaRav Shlomo Eiger (son of Rabbi Akiva Eiger), which contains an account of his visit to the home of the Oruch Le'ner, we learn that the number of signatories later rose to around three hundred. The letter was reprinted many times in the pages of the chareidi publications, where it was regarded as the first move in the shift from a defensive to an offensive stance.

A republished collection of Shomer Zion Hane'eman

Der Treue Zions-Wachter

Undoubtedly, the field of literary polemics had provided the early reformers with a powerful means of influencing ordinary, unlearned German Jews. What could be more natural for those schooled in the new ways than to put the power of the printed word, which had played such a crucial role in the spread of modern ideas across the continent, to their own use in bringing their program to as wide a Jewish audience as possible?

Awareness of the danger of allowing the reformers' ideas to be the only ones in print led the Oruch Le'ner to found the first modern chareidi periodical. The first issue of Der Treue Zions-Wachter was published in Altoona in July 1845, just over a year after the conference in Braunschweig.

An editorial in the first issue addressed some of the more moderate participants in that conference with the following blunt challenge. `Our religion is Divine and eternal and we are at odds with the ambitions of the reformers, who do not even constitute a religious grouping amongst Jewry, but are instead a foreign growth in the vineyard of Beis Yisroel, who have no connection with Judaism. To reformers of Philippson's ilk, who believe in Divine revelation to our nation, we ask: `If that is so, why should we make changes?'

To the party of Fraenkel of Dresden and his group, we turn [with the question]: `Although you regard the Torah and the Talmud as valuable possessions, tell us clearly! Do you not believe in their holiness? And if you do, what business do you have with religious reforms? How long will you hover between two camps?'

The journal's first editor was Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Enoch but HaRav Ettlinger closely supervised its production and his articles often graced its pages. The journal also had a Hebrew supplement, Shomer Tziyon Hane'emon, which, although it did not address itself directly to the contemporary problems of German Jewry, clearly demonstrated through its pages of halachic debate and elucidation, chidushim, teshuvos and poetry, that the Torah world was alive and well, flourishing all over Europe and beyond. (Indeed, many of those at whom the paper was aimed neither understood Hebrew, nor possessed the necessary background to appreciate the contents of the Hebrew supplement.)

The Oruch Le'ner collected contributions from rabbonim in Eretz Yisroel, France, Russia, Denmark, Poland and Hungary, as well as from all over Germany. Many of his own teshuvos were first published in the pages of Shomer Tziyon Hane'emon. The journal had a high standard, both in terms of the material and its presentation.

In his introduction to Oruch Le'ner on Sukkah, HaRav Ettlinger himself refers to its immense impact on German Jewry and its success in reducing the reformers' prestige `until they stopped gathering, as they had done (referring to the cessation after only three years of what were supposed to have been annual Reform conferences).

Upon receiving one of the first copies of Der Treue Zions- Wachter (the Hebrew supplement had not yet started to appear), which the Oruch Le'ner had sent to Pressburg, accompanied by an explanation that the journal had to appear in German rather than loshon hakodesh so that ordinary people could understand it, the Ksav Sofer responded, `I will tell you my friend, although you are right about the times demanding it, in my humble opinion it is still not correct that rabbonim who occupy positions of authority, who fear Hashem and respect His Name, who stand guard on behalf of bnei Yisroel, to strengthen religion, our faith and our language, should issue and sign a public notice in German. It looks, chas vesholom, as though they despise loshon hakodesh and agree that there is no need for it in the present times... Who will try to teach his son loshon hakodesh if he sees G-d fearing rabbonim using the gentiles' language?

?It therefore seems to me that it would be good in the eyes of both Hashem and the public if the same content that appears in German would be translated into loshon hakodesh and the two versions printed together. Then it would appear as though the German was simply a copy of the loshon hakodesh [printed so that ordinary people could understand... It may be that this [issue] is not regarded as a blemish in your country but in Hungary and the surrounding lands, it is regarded as such, according to our acquaintance with the population. Therefore, please forgo your honor and do not take exception to me for having offered my advice when I was not asked to do so.'

The journal appeared as a weekly for five years and after a year's interruption, continued as a fortnightly for a further six years. Before it ceased publication though, HaRav Shimshon Refoel Hirsch zt'l had launched the monthly Jeschurun. This was joined in 5620 by HaRav Meir Lehmann's Israelit and in 5630, the weekly Die Juedische Presse, edited by Dr. Enoch and Rabbi Yaakov Hollander, another talmid of the Oruch Le'ner, began publication.

The appearance of additional such reading material may well have been a factor in the discontinuation of Shomer Tziyon Hane'emon, every issue of whose appearance made extra demands on HaRav Ettlinger's already heavy schedule of supervising his communities, teaching his talmidim and preparing his seforim.

The grave of HaRav Ettlinger

Dissociate Yourselves!

Although the vociferous debate over the question of Orthodox secession from kehillos which numbered reformers amongst their heads did not open until 5636, four years after the petiroh of the Oruch Le'ner, it is worth mentioning briefly because it was the natural progression in the fight to preserve the integrity of Orthodoxy and also because there is an unimpeachable source which suggests what the Oruch Le'ner's stand would probably have been.

With the passing of the law of secession (Austritt), HaRav Hirsch called forcefully for all G-d fearing Jews to dissociate themselves from kehillos that included reformers, lest their continued membership lend credence to the reforming ideas, implying that it was possible for Orthodoxy and Reform to practice Judaism together, as two valid alternatives.

His ruling was opposed by HaRav Yitzchok Dov Halevi Bamberger zt'l, the Wurtzburger Rov, a leader of Orthodoxy in Southern Germany, where he headed the famous yeshiva in Wurtzburg, and also a mechutan and very close friend of the Oruch Le'ner. He ruled that there was no obligation to secede from a kehilla that was fundamentally Orthodox and was merely officially considered as part of an umbrella community whose leaders included reformers.

There were many great talmidei chachomim in Germany who followed HaRav Bamberger's psak. In a letter to HaRav Bamberger, the Maharam Schick zt'l, writes `and in reality, the rav and gaon of Frankfort-am-Main [HaRav Hirsch] was exaggerating when he said that the heart of anyone who does not separate from them is not firmly with Hashem and His Torah, for it is not so.'

In fact, HaRav Mordechai Halevi Horowitz zt'l, one of the Oruch Le'ner's sons-in-law, took up the rabbonus of the official community in Frankfort after consulting several rabbonim and conferring with his brothers-in-law. He saw success in his efforts in the post.

HaRav Ettlinger's view is clear from the following report. In a letter to his own brother, HaRav Shlomo Eiger zt'l gave an account of his visit to Altoona, where he had been invited by HaRav Ettlinger. He had shown the Oruch Le'ner a pamphlet he had written on the subject of dissociation from the reformers, in which he ruled that this was obligatory, `for they are not to be considered as belonging to Jewry for anything.' However, HaRav Eiger wrote that, `although they had to agree to it as halacha, they were unwilling to take concrete steps. For the av beis din of Altoona, with all his piety and the work that has been done by him to defame the actions of these wayward ones, through the writings in Dr. Enoch's Shomer Tziyon, was afraid to take actual measures against the wicked ones who rule him, because until now, they honor him and elevate him, as is the customary way of the men of Ashkenaz.

"And although most of the wealthy men are men of discord, around whom the spirit of apostasy hovers, the foolish ones have not presumed to oppose the elder who has acquired Torah wisdom and they treat his rabbonus in the time honored way. I was very impressed by the old customs which they practice and the amount of time spent on the tefillos (which was a lot more than in all the botei knesses in Poland), [which were said] word by word. This is why the German rabbonim are reluctant to publicly antagonize the wealthy laymen by publicizing such a ruling concerning the heretics, so that the former do not openly join the company of the latter, destroying any good portion that still remains among them.'

Rabbonim who had watched in horror as sympathy for reforming ideas infiltrated G-d fearing kehillos, were understandably very reluctant to force a break, lest this drive many who were content to remain officially within the fold of Orthodoxy squarely into the reformer's camp. However, while each kehilla was a obviously a different story, HaRav Hirsch's approach succeeded to such an extent in Frankfort that Rabbi Bernard Drachman, an American visitor to the community a year or two after HaRav Hirsch's petiroh, found that, `while the Orthodox Jews were not in a majority even in Frankfort, they were so superior in their zeal and fervor that they left their impression on all of the city's Jewish life.'

Conclusion: Looking to the Future

Despite the Oruch Le'ner's valiant battle, and the generation of talmidim he raised who followed in his footsteps, he realized that there was no way back for German Jewry and that its days as a strong center of Yiddishkeit were over. Even when parents desired to raise their sons to become talmidei chachomim, the pressures and influences affecting the youth made it impossible for them to succeed in doing so.

There remained, to be sure, a number of great and righteous German talmidei chachomim, whose true stature would have been appreciated had they lived in other lands.

The Seridei Eish wrote, `It ought to be recorded for posterity that amongst the German rabbonim were tzadikim, pious men and men of holiness, to whom multitudes would have flocked in other countries, to benefit from the radiance of their Torah and yirah,' (ShuT Seridei Eish, cheilek II, siman 53). They are not better known today partly because of their own deep humility and partly because it became the practice to look askance upon all German Jews. On more than one occasion, the Oruch Le'ner himself had to take pains to do away with this impression. Nonetheless, whatever the achievements of determined individuals, there was no future for a large center of Jewry in Germany.

Awareness of the tragic situation led the Oruch Le'ner to view the fledgling yishuv in Eretz Yisroel as a possible means of salvation. If Jews in Europe would support the talmidei chachomim who had settled and were continuing to settle there, a strong Torah center could develop, untainted by the scourge of the "enlightenment," which could then sustain Jewry in all the centers of its dispersion.

This was the kernel of the Igeres Hakodesh which was issued and signed by HaRav Eliyahu Gutmacher zt'l, and the Oruch Le'ner, further discussion of which belongs to a more detailed survey of the Oruch Le'ner's extensive work on behalf of the yishuv in Eretz Yisroel.

Eastern European Jewry witnessed the tragic pattern of events in Jewish Germany with a heavy heart and a sense of foreboding. The emancipation and exposure to gentile culture was far slower in arriving there and even when it did, the opportunities it offered for entering gentile society were far more limited than in Germany — western liberalism never penetrated the Russian Empire — and the desertion of Torah in eastern Europe found other forms.

However, the German example naturally led rabbonim to adopt every possible stringency in preventing any repetition of similar events there. In confronting some of the problems posed by the modern world, German Orthodoxy was thus necessarily a pioneer. Many of the works left by the fighters against Reform continue to inspire and strengthen the faith of Jews all over the world today.

Acknowledgement: Virtually all the material used in this series of articles has been extracted with permission from Rabbi Yehuda Arye Horowitz's extensive biography of the Oruch Le'ner which appears in the recent new edition of Sha'alos Uteshuvos He'Oruch Le'ner, published by Devar Yerushalaim in 5749.

|