| | NEWS

Bearer Of The Undying Torch: An Appreciation of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman zt'l, in the Seventy-fifth Year Since His Petiroh

By Moshe Musman

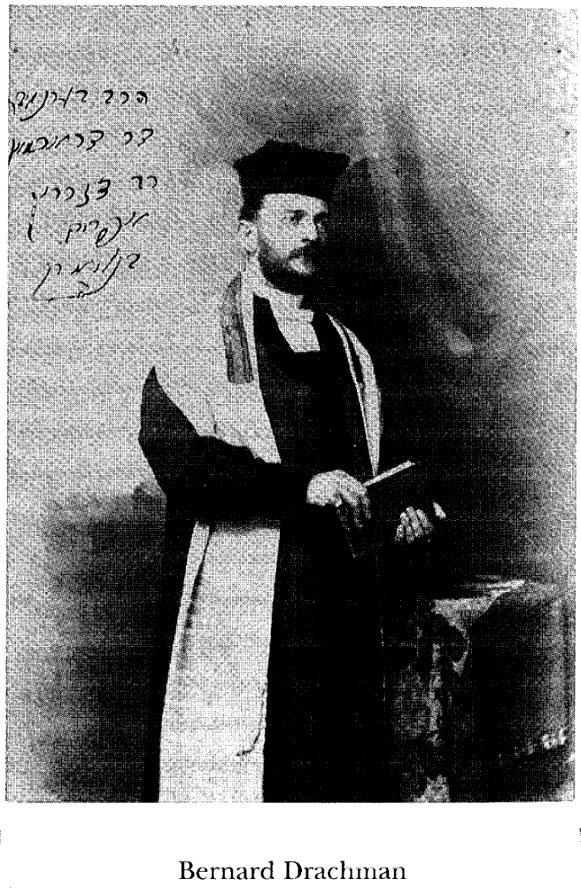

Rabbi Drachman as a young rabbi

The story of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman, who passed away over seventy-five years ago, contains important lessons for understanding about the survival of Torah in the spiritually barren and desolate land that America was a hundred years ago. Rabbi Drachman grew up in a thoroughly American environment, but he nonetheless became firmly and deeply committed to Torah true principles that were, in his person, completely at ease with his all-American heritage. Rabbi Drachman saw, with a fresh and open American eye, the flowering of HaRav Hirsch's Frankfurt, as well as the vitality of eastern Europe. He attended the funeral of Sir Moses Montefiore, officiated at the funeral of Harry Houdini and was on familiar terms with Seth Low, one of the legendary presidents of Columbia University. He also translated Hirsch's The Nineteen Letters and was responsible for Mordechai Kaplan's dismissal from his post as a rabbi in New York City in an Orthodox congregation solely because of the latter's heretical views. His fascinating story helps us understand some of the important roots of the American Jewish community.

Almost all the material in this article is based on Rabbi Drachman's autobiography The Unfailing Light.

The Breslau seminary

Part II

New Experiences in the Old World

One of Rabbi Drachman's earliest impressions of the city of Hamburg, where he disembarked at the end of Av, 5642 (mid-August 1882) was of the very different type of Jew that was to be found in Germany. In the dining room of his hotel he was favorably impressed by the fact that most of the neat, darkly clothed men wore yarmulkes and that many of the women wore sheitlach. He saw men washing their hands and pronouncing a blessing before sitting down to eat a piece of bread and groups of at least three men bentching audibly. "It was," he writes, "a demonstration of genuine, living Judaism such as I had not witnessed in America." This was his sentiment towards much of the day-to-day Orthodox Jewish life in which he was to participate during his sojourn in Germany.

His first Shabbos was spent with his mother's brother and his family in the village of Nordheim, a typical rural central European Jewish community consisting of just eighteen families. In one beautiful paragraph, he vividly recalls the deep impression which the simple sincerity of the Shabbos tefillos in the small village synagogue made upon him.

"I recognized the utter sincerity of these simple souls, that to them their Judaism was a compellingly real and vital faith, an indissoluble part of their thought world, in fact, their very lives. Nothing there of the split and divided souls, in which contradictory and antagonistic ideologies were struggling for the mastery; nothing of the mechanical acceptance of a superficial tradition... nothing of the revolt against the time-honored religious practices of Israel... shown by the substitution of utterly unauthorized innovations and alterations, which I had observed in the great metropolis of America and which I knew to exist... in the great cities of the Old World as well. The Judaism of Nordheim was simple, clear and unquestioningly loyal. In the little synagogue on that first Friday evening and during the rest of the Sabbath observance on the morrow, I felt this genuineness and axiomatic loyalty and the perception and appreciation thereof penetrated to the very depth of my heart. I began to understand what real Sabbath observance is and what a hallowing and uplifting influence upon one's entire personality and life outlook it possesses."

A view of Witzenhausen, a small town in central Germany, probably larger than Nordheim

This was only the first of many such experiences among the Jews of the Nordheim and the vicinity. These encounters showed the young American the spiritual wealth of Judaism when it is lived normally and fully, more than any formal lectures could. After experiencing the Yomim Noraim and Succos in the special atmosphere of Nordheim, it was time for the trip to Breslau.

Though praising his teachers' great erudition and Jewish scholarship, Rabbi Drachman detected differences between them in their devotion to Judaism (it is unclear whether his intention is Jewish practice or ideology). It should be noted that in the world of German Jewish scholarship of those times, opposition to Reform was sufficient qualification to be regarded as a defender of traditional Judaism. Like the Orthodox, the advocates of the `historical' approach also objected to the wholesale redesigning of Judaism which Reform was carrying through. However, what the main stream latter school of thought really sought (it is now clear in retrospect) was a way to provide legitimization for changes or `development' in halacha, in the spirit of the modern enlightenment, without depriving traditional Judaism of credence, nonetheless stopping short of acknowledging it to have been Divinely revealed. Nonetheless, in those early and unclear days there were individuals whose commitment, it is evident even in retrospect, was to the true and traditional concept of Torah.

To the masses of Western European and American Jews, whose own Jewish education was usually scant at best, the real and great differences between the Orthodox and `historical' outlooks (the former unequivocally and completely accepting that Torah Shebe'al Peh is also min haShomayim, while the latter rejecting this), were not as apparent as they are today, when the Conservative Movement has amply demonstrated that the ultimate depth of its commitment to Torah is hardly deeper than that of the Reform movement.

The young Bernard Drachman was committed to Torah Shebe'al Peh and halacha, and remained so throughout his life, and he had difficulty reconciling what he saw as Heinrich Graetz's `championship of Traditional Judaism' and `uncompromising opposition to Reform innovations' with Graetz's favorable attitude to Bible Criticism!

While pursuing Jewish studies at the Seminary, Bernard Drachman also studied Semitic languages and Philosophy at the Breslau University.

During the Seminary's vacation periods, the young rabbinical student spent time with his relatives in Nordheim, as well as visiting some of the other European Jewish centers. With his cousin, he paid a visit to Frankfurt-am-Main, the home of the congregation of HaRav Shamshon Raphael Hirsch zt'l. While the Orthodox Jews were not the majority in Frankfurt, he found that they were so superior in their zeal and fervor that they left their impression on all of the city's Jewish life. The cousins attended a learning session of fourteen or fifteen members of the Hirsch kehilla. The sight of a group of laymen so imbued with love of Torah as to devote a great part of their time to its study, filled the young American with respect and admiration.

Eastern Europe

Completely different from Germany was Galicia, Poland (which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire) where Bernard Drachman travelled to visit his father's family after his second year of studies. In traveling eastward, the overall impression from the train of `smiling, well cultivated fields, ... straight, smooth roads ... and strongly constructed houses' of the German countryside, gave way to a landscape that had an aspect of `wildness and primitiveness' and which seemed to lag hundreds of years behind Germany in its development.

The Eastern European Jews with their payos, full, long beards, fur-edged hats and long black robes that reached to their feet, were as new a sight to the young traveller as the landscape was. He embraced them. "I saw that Judaism had survived in these regions with a strength and naturalness which it did not possess in the lands of the Western world. I had met many Orthodox Jews in Germany and some even in America but [even] the strictest and most observant of them were not Jewish in the sense in which these Jews of Galicia were... Everywhere [else] there was an attempt to lessen the distinctiveness of the Jew... to reduce Judaism to a mere matter of religious belief... here was a large Jewish group...absolutely frank and open in the complete preservation and maintenance of their Jewishness."

On a Friday afternoon in the great market of Cracow, Bernard Drachman witnessed an amazing sight. Most of the merchants of agricultural products and wares were Jews, while most of the customers were Poles. Together, crowds of them filled the vast square in the center of the city conducting their negotiations, bargaining and selling. Suddenly, at about five o'clock, all business ceased, stands closed and sellers and customers alike began streaming away from the market. Within a very short time, the great square stood silent and empty. The approach of Shabbos had summoned the Jews away and with their departure, the market closed.

Over that Shabbos in his hotel, Bernard Drachman was a fascinated listener to the Polish Jews' Torah discussions, conversations on general affairs and recounting of anecdotes. While in appearance they seemed to be from another world, he found that they possessed keen and bright minds and had pearls of wisdom on their lips, while all their conversation was uplifted by the spirit of Shabbos, which elevated it beyond the merely intellectual or amusing. The following day, he visited the grave of the Ramo in the Cracow cemetery. After visiting Levov and travelling on east to meet members of his father's family, who lived in Brody, near the Russian border of Galicia, he began the long trip back to Breslau.

His third year in Breslau was the most intensive in terms of Jewish studies and before his departure from Germany, he obtained a smicha from the rabbi of one of the two synagogues in Breslau and a certificate attesting to his attainments from the Seminary faculty, and a doctorate from a German university based on a paper he wrote for a competition in the Seminary.

Before crossing the Atlantic, he also paid a visit to England. Calling on the acting Chief Rabbi, Dr. Herman Adler, he was received with courtesy and kindliness, informed by the rabbi that he was about to leave for the funeral of Sir Moses Montefiore, which was to take place in the Bevis Marks Synagogue and invited by his host to travel with him in his carriage. After a short stay in England during which he met some of the other leaders of Anglo Jewry, picked up another smicha and viewed London and Liverpool, he departed for America, arriving almost exactly three years after his departure, in late August 1885.

New Problems in the New World

Happily reestablished with his family, Rabbi Drachman had to grapple with a severe predicament. He had been sent to Germany and supported there by an institution affiliated with the Reform Temple Emanuel and, while none of his sponsors had exerted the slightest pressure upon him to shape his views or policies in any way, it was naturally expected that he fall in with their religious viewpoint. Rather than putting him in sympathy with them, however, his studies and contact with Jewish religious life in Germany had convinced him "of the bindingness of authority and tradition upon the individual Jewish conscience and of their indispensability for the proper interpretation and fulfillment of the Jewish faith," convictions which were anathema to the Reform leadership. It was clearly impossible for him to ally himself with them, yet he had received great kindness from them and he recoiled from the idea of seeming ungrateful and unappreciative.

He accordingly visited several of the Emanuel Seminary trustees to express his gratitude to them. In his conversations, he steered clear of discussing his religious views. They expressed their desire to hear him preach in their temple and shortly afterwards, he received a formal written invitation to officiate as guest speaker on the following Shabbos. After having davened at home before setting out for the temple, Rabbi Drachman delivered his sermon bare headed, in accordance with Reform practice, but he pointedly refraining from mentioning Hashem's Name because of this. His non participation in the service and his avoidance of uttering Hashem's Name with a bare head did not go unnoticed and he was subsequently informed that his principles precluded the possibility of his becoming a rabbi at Temple Emanuel.

Despite his evident abilities as a speaker and writer in English, Rabbi Drachman's immediate career prospects seemed pretty bleak. "It almost seemed...that... there was no demand in America for an American born, English speaking rabbi who insisted on maintaining the laws and usages of Traditional Judaism even in the service of the synagogue." Reform had conquered almost all of Jewish life.

There were a few Orthodox congregations of Americanized immigrants whose rabbis were English speakers but none of them was seeking a rabbi. Although there were sizable groups of Eastern European immigrants living on New York's Lower East Side and in other densely populated districts of the cities, congregations of this type were composed of Yiddish speakers and they sought rabbis of their own type. "They were strange to me," writes Rabbi Drachman, "and I was even stranger to them. I preached by invitation in a few of these synagogues but, while my sermons made considerable impression and there was a great deal of admiration — as well as amazement — for me as an American young man who had renounced Reform and was energetically championing the cause of the ancient traditional Jewish faith, these sentiments did not materialize in the form of a call to the rabbinate of any of these congregations."

During this period, Rabbi Drachman spoke to meetings of Jewish organizations and submitted articles to Jewish publications. He stressed the duty of American Jews to remain loyal to their ancestral faith and maintained that no reforms whatsoever were necessary in order to practice true Judaism and experience its spiritual beauty and elevation. Rabbi Drachman had no thought of modifying his convictions for the sake of gaining employment and he decided that if no opening presented itself that was in harmony with his religious views, he would abandon the rabbinate and seek some other field of employment.

End of Part II

Click here for Part I

Click here for Part III

|