The Building of Radin Yeshiva as it appears today.

Do you know who understood him well? The acclaimed mashgiach HaRav Yeruchom Leibowitz zt'l, who was mashgiach in Radin before his arrival in Mir. Reb Yeruchom saw and understood with whom he was dealing. He comprehended that the Chofetz Chaim was unique in his entire generation, that he was holy, and way above everyone else. He realized that not everyone was worthy of being in his presence, that not everyone ought to be allowed to come before him whenever the fancy took them.

His speech was not understood by all, despite the fact that he seemed to speak so simply, in such a homely and straightforward way. One had to contemplate what one heard, to penetrate to the heart of what he said. Reb Yeruchom understood that and he consequently resolved that not every bochur would be allowed into the Chofetz Chaim's presence. And his decision was actually implemented! Reb Yeruchom was particular that only the outstanding bochurim, in wisdom and understanding, would be allowed entrance to the Chofetz Chaim, for only they were able to grasp something of his intent.

Such a rule left a great number of the other bochurim feeling snubbed and inferior. Hitherto, they had felt as though they were members of the Chofetz Chaim's household, able to go in and speak to him whenever they desired, without anybody telling them when or what to say or how long to say it for. And now there was a new system! However, Reb Yeruchom stood by his resolution with firm decision."

"I heard this story when I came to learn in the yeshiva in 5690 (1930) as a young lad," says Reb Shlomo. "At the time, I didn't understand what Reb Yeruchom had fought so determinedly for. Why had he stood by his decision so obstinately? Let them go in, let them come, why not? After a number of years had passed however, I understood. Not everybody was either capable or worthy of understanding the Chofetz Chaim. Only the gedolim understood him correctly. Reb Yeruchom, for example, or Reb Elchonon Wassermann Hy'd, who used to spend the whole period of the Yomim Noraim in the vicinity of his great master. But we, of such puny stature?"

A Lost Opportunity

And yet, what I can do is relate some of my memories. Today we regret not having made use of the light while we had it. We regret not having tried to draw out more and more from him, not having delved deeper. We are sorry that we did not try to catch more, and to work through everything thoroughly. Today we are full of regrets. Oh! So full of regrets. This is despite the fact that I arrived in Radin at the very end of his life, in 5690 [the Chofetz Chaim passed away in 5693 (1933)] when he was already at an extremely advanced age and was ailing and terribly weak. However, had we been wiser, we would have made more of an effort to try and understand. It is with regret and certainty that I tell you we did not make the most of the Chofetz Chaim while he lived.

There were about two hundred bochurim in the yeshiva. By then the Chofetz Chaim hardly ever went out of his house. Old and frail, he would sit in his room reflecting upon divrei Torah as much as he was able to in his condition. He would speak every erev Shabbos after kabolas Shabbos. Only around twenty bochurim, perhaps a few more, would go in to these talks. We simply didn't use the Chofetz Chaim as we might have done. The reason for it was that we were used to having him there. Since we had merited living at the same time as him, and in close proximity too — within walking distance — we imagined that was how things would always continue. So why hurry to try and fathom the depths of his thoughts or to fully comprehend his meaning? The time would yet come when we would listen better and try to understand more. So we thought, in our shortsightedness. Routine played its part too. We took his being there for granted, as something that was self understood. Today we disciples are so few in number and so regretful.

Had our masters' disciples comprehended, they would have written down on the same day what they heard from him every Shabbos. It would then have been possible to print a sizable and valuable volume on each of the Chumashim, for words left his lips like the swelling flow of a wellspring. However, in our youthful folly, we thought that we would always be able to warm ourselves by his illumination and that the holy fire would burn forever, never going out."

The Chofetz Chaim and Klal Yisroel: Mutual Devotion

"The Chofetz Chaim had a special radiance," Reb Shlomo continues, "and a noble countenance. There was an expression of tenderness upon his gentle and smooth face and the loveliness of genuine kedusha. Although he conducted himself with utter simplicity and looked very ordinary with his small, short stature and his furry Polish hat on his head — just like an ordinary Polish Jew — his face radiated a light that words cannot describe. He was someone really special. His name had already spread around the world in his lifetime. People the world over trembled at his utterances. They loved and admired the elderly, holy Jew who lived in Radin.

I remember being told that when the Chofetz Chaim travelled to take part in the famous Grodno meeting of the Vaad Hayeshivos, the organization which he set up and looked after, masses of people took to the streets to meet him, to try to see him and to obtain a blessing from his lips. As he passed through the streets, one woman ran over and kissed the fringe of his coat. That was the extent of the love that everyone felt for him.

For his part though, he cringed at any honor extended to him. On the few occasions that they carried him from his house to the yeshiva, during the period when I learnt there, it was forbidden for anyone to stand in front of him, where he could see them as he passed by in the street. This was in order that there not appear to be any crowding around him or an entourage following him, to honor him. Everybody had to go behind the chair in which he was being carried. The main thing was for him not to notice them.

I remember on one of the Shabbosos during the winter of 5691 (1931) when we went in to hear him speak between kabolas Shabbos and ma'ariv. The Chofetz Chaim sat in his place in his room and next to him sat the Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Moshe Landynsky zt'l. We bochurim who had gathered around the table, were waiting to hear him speak.

The Chofetz Chaim suddenly began speaking about taharas hamishpocha. `We must see that the laws of family purity are observed,' he said. `The situation is getting worse and we must mend the breach.' As he spoke, he grew more and more excited and enthusiastic, repeating himself in ever louder tones. `We must ensure that taharas hamishpocha is observed.' He took hold of the Rosh Yeshiva's hand and, fired by holiness said to him, `Reb Moishe! We two are already elderly men and are not afraid of anyone. Let us go from house to house and see that no impure house remains!' As he spoke, a glow of enthusiasm was ignited within him and he said, `Let's set out now to start working.'

Reb Moshe saw how strongly he wished to leave without any delay and that he was absolutely serious in his intention to prepare for a journey. In the hope of calming the Chofetz Chaim down and dissuading him from the bold idea of making such a trip at his age, he said, `Be'ezras Hashem, after Shabbos we'll see. Slowly, slowly, not right now.'

However, unbelievable as it may sound, a day or two after Shabbos, on my way from the apartment where I slept to the yeshiva, I saw a wagon standing next to the Chofetz Chaim's house and I learned that he was planning a trip to Vilna right there and then, in order to arouse the people there and to strengthen the observance of taharas hamishpocha. No appeals to him about the difficulty of the journey helped. The Chofetz Chaim had decided and go he would. An oven filled with coals was placed in the wagon, blankets and cushions were arranged for him inside and thus he travelled to Vilna!

A friend of mine who accompanied him on the journey told me that when he arrived, the Chofetz Chaim called all the rabbonim of the town and the surrounding vicinity and alerted them all to the duty of strengthening the observance of taharas hamishpocha, which they all had to work for. With burning enthusiasm, he called for them all to lend their help. As if this was not enough, the Chofetz Chaim asked to publicize the news that he would be addressing the women of the town in Vilna's Great Synagogue and requested their attendance at the appointed time. Many hundreds of women from all over Vilna flocked to hear the Chofetz Chaim's address. The holding of a special drosho for women inside the Great Synagogue was truly an historic event!

The Chofetz Chaim spoke heart rendingly for an hour about the great importance of the laws of taharas hamishpocha and about the obligation which the Torah had placed upon women to observe them. He urged them to remain steadfast in guarding their holiness and purity. Because he was weak, he couldn't be heard and the gaon HaRav Boruch Ber zt'l was asked to transmit his words in a loud voice. The tzaddik Reb Boruch Ber went over to the aron hakodesh and wept in prayer that he merit repeating the Chofetz Chaim's words exactly as he had uttered them and that he not stumble and convey them incorrectly. He then repeated the drosho for the women. The Chofetz Chaim's enthusiasm for strengthening the weaknesses in kedusha and taharoh was undimmed, even at the end of his life when, though old and weak, he took himself to Vilna to act and to offer encouragement."

Preparation for Marriage

In his later years he would usually spend the time at home, not coming to the yeshiva at all. Only on Yomim Tovim would he come for the morning tefillah, in order to give bircas Cohanim. On those occasions, everyone would rush to grab a place right in front of him, so as to merit a blessing from the mouth of the generation's greatest Cohen.

Very occasionally, word would go round in the yeshiva that the Chofetz Chaim was calling everyone to come over to his house. Naturally, the house would then fill to bursting. People virtually stood on one another's heads in order to hear what the Chofetz Chaim wanted to say.

To this day, I remember one of those occasions clearly. It was on erev Rosh Hashanah 5692 or 5693. We were told that the Chofetz Chaim was calling everybody in. The bochurim immediately gathered together, crowding around him. The older ones sat next to him and the younger ones sat further behind, while we new arrivals were even further away. The Chofetz Chaim sat absorbed in thought, then he began to speak slowly and quietly. `Why don't boys get married? You must marry! Why don't boys marry? Is it because they want to have twelve chairs in their home? What for? It's enough to have one stool for the husband, one for the wife, one for a child, one more for another child and one for a visitor, that's all. So why do boys wait to have twelve chairs? You must marry!'

To understand the Chofetz Chaim's concern, Reb Shlomo explains that there were very old bochurim present, some of them thirty-five years old.

It was very difficult to find a suitable match. Who would look at a yeshiva bochur in those days? Who wanted to marry one? The average Jew in those times was a baalebos and a complete ignoramus, who "knew" only that a man's task in life was to work. Who gave a thought to bnei Torah? There simply wasn't anyone who would agree to marry a yeshiva bochur. The result was a marked disinclination on the part of the bochurim to start with the entire business of seeking a marriage partner, even once they had reached an advanced age.

The difficulties were further compounded because poverty was the rule in those days, especially among those who learned in the yeshivos. Even if a bochur started to meet a proposed shidduch, he would need to borrow clothing from others so as to appear normal and not quite so neglected.

Once or twice a zman, an allowance (chaluka) would be distributed by the yeshiva. Bochurim had to manage on this for the whole zman. They would use it to pay the owners of the houses where they lodged and for the wages of the women who prepared meals for groups of bochurim, each group having its own cook.

I remember one bochur who received a loaf of bread from the lady of the house where he stayed. Each day he would mark the loaf into three sections with his knife and say, `I'll eat this much now and the next part in the evening!' That is the way things were!

On the other hand, the situation had some positive features. The fact that bochurim waited until such an advanced age before marrying meant that they could sit and learn undisturbed, day and night. The responsible ones did just that. Of course, they finished Shas while they were still in yeshiva. A boy could simply sit down in yeshiva and learn and learn for years, until he finished Shas. And more than a few of them actually did it.

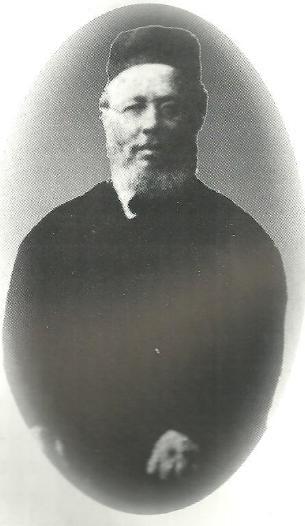

Rav Aryeh Leib, son of the Chofetz Chaim

Today, the times have changed. Around the age of twenty, boys already begin meeting proposed brides. How can they learn Shas in yeshiva? When do they have the time? Admittedly, today the learning is very good and the atmosphere is conducive. There are thousands and thousands of bochurim in yeshivos, boruch Hashem. They are given direction in their learning. They have mentors.

None of this existed in our times. A bochur developed on his own. His environment did influence him but passively, without providing him with a direction or with guidance. That is how it was in Radin, as well as in many other yeshivos. Reb Yeruchom for example, did provide the bochurim in his yeshiva in Mir with some guidance. He made demands upon them. He had requirements. He led and directed them. But in Radin there was nothing like that. If a bochur wanted to develop, he literally had to do it by himself. Those who did, really became Torah giants. They sat and learned for ten or fifteen years. Before they were twenty-eight, they didn't even give marriage a thought!

However, on that erev Rosh Hashanah, the Chofetz Chaim felt it was important to protest waiting so long before marriage. If a suitable proposal came along, it should be accepted and not turned down on account of demands for what were then more than the minimal necessities. It was enough to have one stool for the husband, one for the wife, one for a child, one for another child and one for a visitor!

I remember that the Chofetz Chaim's son, the gaon Rav Leib zt'l, would visit his father from time to time. He would come into the yeshiva and yell at us, `What are you doing here? I'll drive you all out! Get married already! How much longer will you wait here?' But nothing changed. That was how it was in those days.

End of Part I