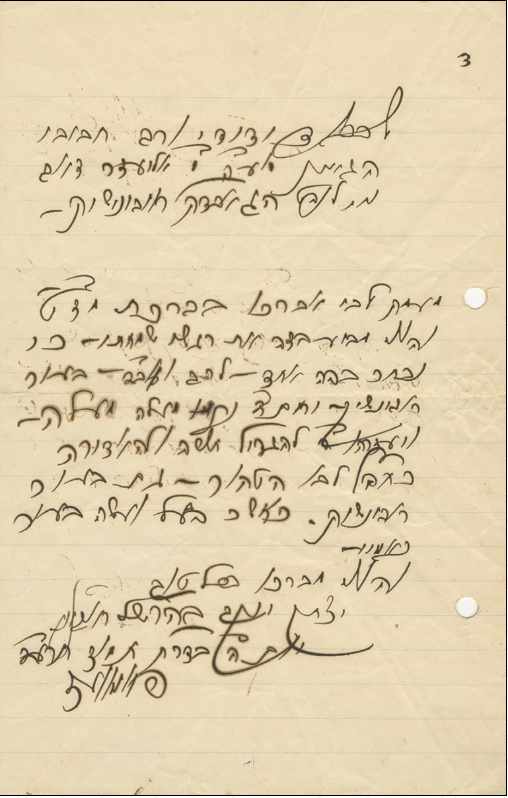

A letter written by R' Itzele Ponovezher

The Power of Pure Torah

R' Itzeleh imparted an aura of unrestricted reason—Torah reason.

Lithuanian Jews relate that one of his finest shiurim was delivered in the Neveizer Kloiz of Kovna. At this shiur, R' Itzeleh presented a hadran which stunned the entire yeshiva world. They said that it represented consummate Torah logic.

Lithuanian Jewry also reserved special definitions and expressions for his chidushim. His chidushim were never merely innovations or elaborations. Each chidush was an earthshaking invention, a brilliant revelation. Each word was a basic rule, and each chidush a penetrating definition. In Lithuania they said that his chidushim were sharp enough to split hairs.

His thoughts were never classified according to their origins. His Torah raged like a thundering waterfall. His great mind did not pause to arrange his words. They said that R' Itzeleh was the greatest mechadesh of latter times. They said, too, that there was not one word of the Torah, or one word in the entire sea of the Talmud and its commentaries, on which he had not formulated a chidush.

Every chidush which escaped his lips was followed by an awaiting gem of thought. His capacity to innovate waged a constant war with his power of speech. This detail, say knowledgeable people, was the only one which distinguished him from his great friend, R' Chaim of Brisk.

Even when he spoke on public issues, his great mind hummed with activity. An eye witness reports:

"He spoke in a conversational manner, without rhetorical devices. As he spoke, brilliant thoughts, which had just that moment blossomed, would clash in his brain, seeking an outlet.."

Early Stages in Learning

When he was still a child, he realized that Torah logic had to be regarded with awe. He would toil arduously to resolve the questions posed by the Tosafos, and refused to consult the Baalei Tosafos for aid. He maintained that Torah study demands maximal exertion of one's reason, one's mind of the logic of the heart.

R' Itzeleh's father, R' Shmuel Dovid, was a successful merchant from Sharshov, who had been blessed with a keen understanding of the inner capacities of his youngest son. He refused to send him away from home, and thus, R' Itzeleh, unlike the other youths of Sharshov, never studied in a yeshiva. "A yeshiva," his father claimed, "is too institutionalized a framework for the stormy and turbulent mind of my little Itzeleh." It is difficult to know from where the father drew so original a perception. However, in succeeding years, it proved to have resulted from a prophetic spark, thanks to which Knesses Yisroel merited the gaon of Ponovezh.

Indeed, R' Itzeleh's mind required expanses, and was never satisfied with little (in spiritual realms). He also did not recognize the concept of confinement, where Torah matters were concerned. When faced by iron kushyos, he refused to bind the halacha in question, and would not place it in a limiting framework, but would detach the kushya from its root. When a sevoro was crystallized in his bais medrash, he would allow no foreign elements to cling to it, but would examine it in an instant, and purge it in his furnace, quickly revealing its delicate flaws.

His rapid pace and the swift flow of his thoughts made it very difficult for his students to grasp many of his ideas. This fact embittered him during many periods of his life. When he was in Bialystok, the yeshiva's trustees realized that matters could not continue that way, and took urgent measures to change the composition of the student body. The problem was resolved by the establishment of the kibbutz in Ponovezh, which we shall soon describe.

It was very difficult for the average person to dwell in his presence for a long time. "In his company," people would protest, "one can say nothing worthwhile, which has not already been said..."

One who knew him once remarked, "Like most of us, I too did not fully understand his teachings. Each of us merited to taste a few of the crumbs of the exalted table. However, these crumbs, too, were worthy portions..."

His penetrating logic nullified topics which lacked the grandeur of reason. In his youth, he once fell gravely ill. During that period, his doctors forbade him to pursue in depth studies. As a result, he attempted to read some of the Hebrew literature which was then popular in Russia, but was deeply shocked by their shallowness and frivolity. He was amazed, too, that adults could waste their time reading descriptions written only for rhetoric's sake. He threw those books away, and spent the remainder of his illness studying Russian, which was very important to know then, and reading Russian philosophy works, whose logic he highly esteemed.

His familiarity with Russian was a rarity in rabbinic circles of Lithuania, and caused people to cite the joking remark attributed to R' Meir Simcha of Dvinsk, who had said that he was "less jealous R' Itzeleh's Torah knowledge than of his familiarity with Russian. With R' Itzeleh's Torah, one cannot conduct a conversation with Russian officials, but his knowledge of the Russian language is quite effective to communicate with them..."

One of his close acquaintances would sometimes bring him Russian newspapers, which, in the spirit of the times, were very philosophical and replete with allusions. Quickly, he would scan the editorials and the main points of the articles, mumble something about the contradictions they contained, and return to his thoughts.

It is said that he had reservations about mathematics and related subjects because, due to their total dependence on axioms that are only conventional. They may be rigorous, but they lack the full power of free reason.

It was said that one of the geonim of Lithuania once decided to enlighten the world with a magnificent composition on the Talmudic topic of migo, with the possibilities of ne'emanus and koach hata'ana. He secluded himself and worked for two years, probed Torah's depths, purged his soul with "scalding waters," to plumb the depths of the topic.

After the years of toil, during which he thoroughly clarified the issue, he set a date and invited all of his friends to view his new work. When the long anticipated moment arrived, he recalled, to his dismay, that due to his tremendous mental exertion, he had forgotten to record his conclusions in writing.

One cannot know whether this event actually happened. However, it aptly represents the Lithuanian rational approach to "minor" technical matters such as writing and printing.

Machon Yerushalayim, which has compiled many of the writings of the gaon, R ' Zalman Sender of Krinki, possesses many of his manuscripts in which this strange phenomenon is apparent. In a number of them, the end of each line bears no relation to the ensuing one. In each line, there are words or a number of letters missing. When this phenomenon repeated itself in many of R' Sender's manuscripts, the matter was investigated and clarified.

When R' Zalman Sender wrote, his entire heart and mind were so wrapped up in his penetrating thoughts, that he would not notice that his pen had overstepped the bounds of the paper. As a result, he would continue writing on the table, not realizing that it was gradually being covered with chidushei Torah.

This fact surely explains why R' Itzeleh of Ponovezh, the greatest mechadesh of his time, and one of the greatest meshivim of the entire period, left behind very few transcripts from his magnificent legacy of Torah thought. Unlike other great meshivim, R' Itzeleh did not take the trouble to preserve copies of his responsa for posterity. This, though, causes tremendous difficulties for anyone searching for his teshuvos. In order to locate them, one must approach the grandchildren and great grandchildren of those to whom they were sent.

We possess written testimony concerning his attitude towards his writings from someone who entered R' Itzeleh's home and found "a notebook which was lying in the corner of the room... which contained remarkable chidushim on Yerushalmi, Zeraim..."

Another reason why he did not write much, stems from the lack of co- ordination between his mind and his other organs. His mind buzzed with endless amounts of ideas, and it was very difficult for him to limit himself to writing which is, by nature, a restricting activity. Even when he wrote, waves of comments, refutations and new thoughts would engulf him, and the version which emerged would lack the natural organization of the written word.

This situation gave rise to a bewildering phenomenon. The very fact that R' Itzeleh's teaching flowed like a perpetual spring was what doomed his endless produce to future oblivion.

After his death, one notebook, containing chidushim on Yerushalmi, Zeraim, as well as fifty-four chidushim on the topic, "petzua daka, was found. These, too, became lost over the years.

*

Part II was originally published in the issue of Vayakheil, 5754.

The most momentous milestone in R' Itzeleh's life was reached twelve years after he had begun to preside as rav in Ponovezh. During that period of gloom, darkness and mist for the Jews of Russia, the most preeminent and the last Torah institution in Lithuania was established: the kibbutz for superior yeshiva students in Ponovezh. This institution, which was one of the most magnificent the Lithuanian Torah world had ever known, merited R' Itzeleh's full concern and dedication.

The wealthy Mrs. Gabronski, daughter of the famous gvir, Kalman Wissotsky, owner of the world renowned tea empire, sought to perpetuate her late husband's memory by establishing and supporting a kibbutz for elite students. For this purpose, she journeyed to the home of the gaon of the generation, "the expert in yeshiva matters," as she called him, R' Chaim of Brisk, and asked him where to situate this institution. She had three choices: Brisk, Vilna or Ponovezh, which were all central cities.

R' Chaim explained the factors she had to consider:

"The success of a yeshiva is dependent on two main factors," he said. "A suitable location and a deserving rav. In Vilna, the suitable rav is Maran, R' Chaim Ozer. However the place is not fitting. Vilna is too turbulent and tumultuous for a yeshiva. Brisk is a suitable location, but the rav is not suitable... However, both Ponovezh and its rav are suitable."

And so, Ponovezh was selected.

The yeshiva was dedicated at an inspiring ceremony, held on Rosh Chodesh Nisan 5669. It took place in the "Glickl's Kloiz," and was named Kibbutz l'Metzuyanei HaYeshivos.

Mrs. Gabronski promised to forward the phenomenal sum of five hundred and sixty rubles a month for the support of the twenty select students of the kibbutz, as well as for its head, the mara de'asra of Ponovezh. The eight married students received thirty rubles a month, and each one of the twelve students, fifteen rubles a month. It goes without saying that no other Torah institution in Lithuania received such generous support.

Those accepted in this kibbutz were truly the elite of the Lithuanian yeshivas. R' Itzeleh sent letters to all the leaders of the generation, asking them to send him "those who really understand," before whom he could reveal all. Every one who was accepted, was admitted only after a supreme effort. The achievement of being accepted was in itself an indication that he was a gavra rabba.

R' Itzeleh put his lifeblood into this endeavor, and his spirit hovered over it day and night. The kibbutz comprised only students who could serve as receptacles for his great fire, without being consumed by it.

Those were glorious days for R' Itzeleh. All the wellsprings of Torah logic and knowledge of Hashem opened for him. The shiurim which he delivered were not like the standard ones of the yeshiva world. They contained a concentrated treasury of Torah's keys, chapter headings and basic rules. Day and night, Torah minds buzzed in the "Glickl's Kloiz." It was a new stage in R' Itzeleh's life, and one who is familiar with his writings, can easily discern, in them, the difference between the pre-kibbutz days and the kibbutz days.

The idea and framework of the kibbutz raised the stature of bnei Torah. In the kibbutz, the exalted level of its leader blended with the fact that the bnei Torah were also "wealthy" and of course did not eat teg.

This "wealth" also caused the students of the kibbutz to acquire a strange title. During those days, yeshiva students were called "orimeh bochurim"—poor boys. This expression became so entrenched, that it was transformed into a noun. Thus, in Ponovezh, students who achieved some sort of "wealth" were called "reiche orimeh bochurim." Ponovezh was also the first place in Lithuania where baalei batim, even some who were estranged from Torah, fought for the honor of situating so glorious an institution in their private quarters!

The fact that the kibbutz in Ponovezh was financially established, had a tremendous impact on its learning schedules. The strict rules of the kibbutz were quite unusual, and the fact that they were enforced by deducting from the salary strengthened their validity.

The most amazing amendment was that the members of the kibbutz had to be totally subservient to the authority of R' Itzeleh, and were forbidden to leave the city without written permission from him.

Another of the basic amendments says:

"Everyone must arrive on time at the beginning of the zman. The first time a student comes late, money will be deducted from his salary for each day he misses. The second time he comes late, an entire month's salary will be deducted. The third time, he will be expelled from the kibbutz, and no excuses or claims that his late arrival was beyond his control will be accepted, for the money was given with this condition attached.

"The members of a kibbutz are forbidden to leave the yeshiva during the zman. In extenuating circumstances, the student must consult the Gavad, and if he feels that the reason is justified, he will grant the student written permission to leave. No student will receive more than two weeks of vacation, once a year."

R' Itzeleh struggled to maintain the kibbutz, even when the world was in a state of turmoil. In 5675 (1915), when battles raged on the Eastern front, the kibbutz was expelled and forced to leave Ponovezh. R' Itzeleh and his students fled to Lutzen and to Mariopel, where the kibbutz continued to function in all its glory, despite the burning flames which surrounded it. In those conditions he even gave a shiur every day, even though in quieter times in Ponovezh he gave a shiur only three times a week.

Throughout that period, Mrs. Gabronski continued to support the yeshiva as she had promised. When the Bolsheviks gained control of the country and the property of its citizens was confiscated, the stipends were curtailed, and the kibbutz closed. Its students dispersed, each in search of his own source of livelihood.

At the end of the war, R' Itzeleh returned to Ponovezh, broken in body and in spirit, taking with him one remnant of the glorious kibbutz, a student named Zeev Kornitzer. Together, they stubbornly continued the tradition of the kibbutz, despite the Bolshevik ire they incited.

The authorities, however, did not permit R' Itzeleh to resume the kibbutz, despite the fact that they deeply esteemed him. He died on the twentieth of Adar, 5679 (1919), filled with pain and anguish. With his death, the magnificent Torah enterprises of Lithuania, also ceased to be.

His Biography

R' Itzeleh, the son of R' Shmuel Leib Rabinowitz, was born in 5614 (1854) in Sharshov, a city in the region of Grodno. His father was a prominent and wealthy merchant, who was also a talmid chochom who devoted set hours to Torah study.

When Itzeleh was only seven, he had already studied Kesuvos with Tosafos under the tutelage of R' Benzion, a young man from Bialystok, who was stunned by the brilliance of the youth. As a result of this remarkable feat, Itzeleh soon became known as an illui. During that period, the Ohr Somayach lived in Bialystok, and R' Benzion would delight him, every now and then, with the riddles of the young illui of Sharshov. R' Meir Simcha thoroughly enjoyed these riddles, and until his final days, whenever he recalled the divrei Torah of R' Itzeleh, (who was by then one of the greatest geonim of the generation), he would joyfully remark: "But that is the youth from Sharshov!"

When R' Itzeleh was only eight years old, his mother died. It is related that he heard his younger brother wailing beside the death bed. Presuming that the child was more distressed by the fact that he wasn't receiving attention than by the terrible loss, Itzeleh left the corpse and calmly occupied his brother by playing with him.

Itzeleh's father, R' Shmuel Leib, did not permit him to study in a yeshiva away from home, claiming that a child with such deep perception was likely to be impeded by the restricting framework of a yeshiva.

When he was fourteen years old, he became engaged to the daughter of a prominent villager from the family of the author of Ponim Meiros. His future father-in-law, though, was not only wealthy, but also very G-d-fearing and refined. During the three years between R' Itzeleh's engagement and the wedding, he studied under R' Yeruchom Perlman, otherwise known as the godol of Minsk, and drank from his wellsprings.

In 5648 (1888), R' Itzeleh was invited to deliver his shiurim in the local yeshiva in Bialystok. However he soon began to suffer from spiritual loneliness. The students of the yeshiva were incapable of understanding him, and he could not adapt his shiurim to their level. As a result, the administrator of the yeshiva, R' Shmuel Lifshitz, the brother-in-law of R' Meir Simcha of Dvinsk, decided to alter the composition of the yeshiva, and to accept only very talented and bright students. However his plans did not materialize, because R' Itzeleh was invited by the Alter of Slobodka, R' Nosson Tzvi Finkel, to his illustrious yeshiva.

In 5649 (1889), he began to deliver shiurim in the yeshiva, and his fame grew. Soon, the entire Torah world knew of his brilliance.

His name is mentioned countless times alongside that of R' Chaim of Brisk. Lithuanian Jews said that R' Itzeleh and R' Chaim of Brisk followed similar thought patterns. However, while R' Chaim stressed comprehension (havono) of the text, R' Itzeleh's approach entailed logic. R' Chaim demanded that one know "what" was said. R' Itzeleh struggled to ascertain the reasons "why" it was said.

In 5654 (1894), after the mussar debate divested the battlefronts of Slobodka, he left the yeshiva and began to preside as rav of Grozad, a village in the region of Carteinga. It was there that he founded the yeshiva whose seeds had been provided by R' Nosson Tzvi of Slobodka, which included ten students, among them R' Naftoli Trop.

After serving a year and a half in Grozad, R' Itzeleh was invited to become rav of Ponovezh, which was a large regional city, and one of the most central and important locales in Lithuania.

In 5657, R' Itzeleh, along with eight other gedolim, signed the famous proclamation, L'Maan Daas. In it, they expressed their strong opposition to the Mussar movement.

It is worthy to note, though, that this proclamation constitutes one of the most enthusiastic approbations of mussar study! It describes, at length, the importance of the "kav shel chumtin" [an expression describing the value of mussar study, which is compared to chumtin, a preservative]. It says:

"...Great Torah sages, by whose words we live, were not stinting when it came to producing such mussar works as Chovos Halevovos, Shaarei Teshuva and Sefer HaYashar, which are steeped in mussar, middos and practical rebuke, derived directly from the words of our prophets and sages. They continually studied these works in groups or in batei medrash, probing these sacred tomes which are life to those who pursue them."

The co-signers of the proclamation were displeased only when mussar study was regarded as the main thrust of Torah study, and protested that they had "never heard of designating special study houses or yeshivos for the sole purpose of mussar study..."

R' Itzeleh was also very active in the communal affairs of Russian Jewry. He was one of the important participants in the Knesses Yisroel organization of R' Eliezer Gordon of Telz in 5667 (1907). In 5670 (1910) he was one of the representatives as the conference called by the Czar to discuss basic Jewish issues.

He was one of the most enthusiastic early supporters of Agudas Yisroel. Prior to the Founding Convention of Agudas Yisroel, which took place in Katowitz in 5674, the entire Torah world eagerly awaited the reaction of the Chofetz Chaim to the proposed plan. R' Itzeleh and R' Chaim of Brisk journeyed together to Radin to explain to him to importance of the new organization, and their efforts bore fruit.

The General Jewish Congress convened in Sivan, 5677. It was the umbrella organization of all the local chareidi organizations, such as Netzach Yisroel in St. Petersburg, Agudas Yisroel of White Russia and Achdus Yisroel of the Ukraine. During this period, Kerenski reigned briefly in Russia, bringing with him much cherished democracy. However, that same year, the tyrannical arm of the Bolsheviks put an end to this situation.

Kerenski spoke with enthusiasm about freedom of religion, speech and communal organization. Torah Jewry, which had suffered so much oppression, heaved a sigh of relief.

The founding meeting was held in the spirit of the times, and R' Itzeleh, who was the representative of the gedolei Yisroel, was its life force. It was he who signed the proclamations and delivered ardent speeches about organizing Torah Jewry and recognizing the Torah as the supreme legal authority of the entire Jewish Nation.

The Congress and its decisions were also trampled a few months later by the boots of the Red revolution.

At the close of the war, R' Itzeleh returned to Ponovezh and found that his beloved city had been taken captive by the Bolsheviks, who forbade all spiritual activity.

Typhus raged in the city at the time, and R' Itzeleh dedicated himself to rescuing his depressed brethren, trudging from house to house in order to bring them relief. However, he too, fell ill, and on the twentieth of Adar— the month of joy—returned his pure soul to his Maker, leaving behind a bereft Torah world.

Gemora On The Wagon

A bitter Russian night stormed the small village of Shilal and its meager cottages. It was well past midnight, and its mara de'asra, R' Zelig, had just completed his daily share of toil. Joyously, he paced his tiny kitchen. He was deeply satisfied with his accomplishments, that day. "He'ach! Bar pada!"

He had still one matter to arrange before reciting Hamapil. He dipped his quill in his inkwell, took out a sheet of paper which he had saved all week just for this purpose, and began to write, slowly and with deep intent. His eyes gleamed with happiness when he imagined the great benefit he would derive, on the morrow, from this tiny note.

He pinned the note, with great care, on a nail which he had prepared in advance for this purpose. Then he retreated to his bedroom.

When the rebbetzin of Shilal arose, the mara de'asra was already in shul. She rushed to her small kitchen, and removed the note from the nail. Joyously, she read the few level lines.

"Mein neshomoh," the rav wrote her. "In the morning when you arise, please be so kind as to approach Reb Moshe Aharon, the tavern keeper, and ask to let me borrow his copy of Maseches Bechoros. Afterwards, go to Reb Arye the blacksmith, and ask him to be so kind as to lend me his copy of Eruvin. From Reb Aibush the carpenter, borrow Gittin, and from Reb Elchonon, the Elyah Rabbah..."

She, who had eagerly deciphered such letters for years, read the conclusion which appeared in the margins:

"And my dear wife, tell everyone—Reb Moshe the tavern keeper, Reb Arye the blacksmith, Reb Aibush and Reb Elchonon, that as usual, the agreement is still in affect, and that, with Hashem's help, they will have a share in the Torah which I will learn... in their merit"

She folded the note with awe, and placed it in her bag. Then she rushed out to the yard, took her special cart, and made her regular rounds through the village lanes. Happily, she began to collect the gemoras her husband needed for that day, placing them on the cart.

Such was little Shilal. It was a town which had only one Shas, which was divided amongst all its residents. Such was her mara de'asra. He was a man, who, instead of a Shas, had a nail and a sheet of paper in his threadbare kitchen. But Lithuania burned. It raged with a deep love of Torah which glowed amidst its poverty and want.

"Torah said: `Let my lot be with a poor tribe!" (Yalkut Shimoni, Rus)

As a flame clings to a wick, and a suckling to its mother, so Lithuania lovingly cleaved to the Torah hakedosha. From morning to night, the resplendent sounds of Torah study filled its lanes, paths, cottages and courtyards. Every kloiz, every dilapidated shtender and moldy copy of the Rivash, were fortresses of Torah. In Lithuania, Talmudic sugyos ruled the emotions, minds and wills of its residents like kings. They did nothing without it, and longed for no other treasure. Lithuanian Jews had imbibed their love of Torah with their mothers' milk. The lullabies, which modern folklorists confound, were also immersed in the melodies of the beis medrash.

Oceans of chidushei Torah and spiritual treasures hovered in the air of her pathways. Letters in the air, but finding no rest on paper. Wasted potential! Such is the sad reality anyone who is familiar with Torah literature encounters. The Torah of Galicia, Hungary and Poland found wide expression in thousands of editions of responsa literature, while the majority of Lithuania's Torah vanished into thin air.

It was the dire poverty which impeded the great Torah center of the Jewish Nation—a center without a complete Shas, without access to printing presses, and sometimes without ink or quills. Yes, the greatest wellspring of the Jewish Nation, lacked the paper on which to express itself.

One of the most magnificent enterprises of Machon Yerushalayim, is Mifal Chachmei Lita. "This is the last generation which knew Lithuania and drank from its wellsprings," says Rabbi Yosef Buchsbaum, founder and director of Machon Yerushalayim. "Today, there is still an avenue of approach to those communities, and an affinity with them still exits. This is the final generation which knew Slutsk, Eishishock, Kovna and its suburbs. When the channels cease to be, there will be no more means of approach."

Throughout the world, countless numbers of manuscripts which can illuminate the Torah world are concealed and stashed away. Writings, more precious than gold, lie behind bookshelves of "grandchildren" who lack a feeling for them, or in the homes of researchers who have no appreciation of the value of the treasures in their possession. The efforts of Machon Yerushalayim to retrieve these treasures are indescribable, and they make maximal use of every search method possible, leaving no stones unturned. The members of their staff can relate remarkable accounts of how priceless material was salvaged from unfitting hands, and about the amazing siyata d'shmaya which accompanies them on their journeys through uncharted wastelands.

The writings of R' Zalman Sender of Krinki which were found in the hands of an unsuited student, are a case in point. There was the discovery of the great legacy of R' Yonoson Eibeshitz on the entire Shas —a rare treasure, more precious than gold and rubies—which had been hidden among antiques, in the attic of a wealthy man who had an affinity for such items. At first, he recoiled at the thought that his compliance with the Machon would aid the Torah study of students of "black yeshivos." However, the fruits of the stubborn and persistent deliberations between the Machon and the above mentioned gvir are presently delighting the Torah world.

Of course, the two hundred teshuvos of R' Itzeleh of Ponovezh, vestiges of the teachings of the greatest mechadesh of latter times, were also discovered by the Machon. They were acquired through sundry ways, and were published by the Machon under the title Zaicher Yitzchok.

When the gaon, R' Yaakov Ruderman, was appointed president of this great enterprise, he asked that its first publication be the teshuvos of R' Itzeleh of Ponovezh.

R' Yaakov Ruderman passed away while R' Itzeleh's writings were being prepared for publication. Zaicher Yitzchok, though, is dedicated to him.

Imagine this scene: One bright morning an atomic bomb is (cholila) hurled over New York City. The skyscrapers crumble like card decks. Millions of tons of stone and cement disintegrate and, in an instant, bury the ultimate of human achievement: New York City.

Only a few survivors remain. Destitute and alone, they run for their lives. Some perish in anguish. Others, who are stronger, begin a new life amidst the rubble.

One day a survivor returns to the devastation which was once New York. He sees new life budding: laborers, cement mixers, bricks, engineers, blueprints. Man's creative urge is overcoming the damage.

In the horizon, the frameworks of a number of unfinished buildings are seen. Our survivor is amazed by this productivity. His small son observes the scene in fascination. He pulls his father's sleeve and excitedly says:

"How large is this city, daddy! Have you ever seen such huge buildings?"

The child is overjoyed by his discovery.

His father weeps.

Two hundred teshuvos of R' Itzeleh have seen the light of day and are illuminating the Torah world. I expressed my excitement to those who presided over this remarkable feat, and told them how elated they must have been to have participated in so glorious an endeavor. However Rabbi Yosef Buchsbaum explained that happiness is a relative concept, and in that in this case, tragedy overshadowed joy.

Yes, the fact that a few frameworks sprouted forth from the rubble is significant. Two hundred of R' Itzeleh's teshuvos, salvaged from the countless numbers he wrote, are consequential. But one who knew the New York of our analogy in its glory, could only weep when he saw the skeletons. One who knew or heard or read about the magnificent Torah of R' Itzeleh, whose letters and scrolls have vanished into thin air, can only feel bittersweet joy over the publishing of the two hundred vestiges of the priceless legacy of the great rav of Ponovezh, R' Yitzchok Yaakov Rabinowitz, zt'l.

<