This shmuess provides the basic guidelines for success in Torah from one of the greatest leaders of recent times.

In this shmuess, recorded by Rabbi Yisroel Friedman and published in 2000 (5760) nineteen years ago, the Rosh Yeshiva describes the difficulties, the temptations, and the struggles that bnei Torah once endured, and those that we encounter today. The shmuess includes instructive anecdotes about gedolei Torah, guidelines to a ben Torah on behavior, the correct relationship between a rav and a talmid, and how to acquire true and solid Torah knowledge.

Part I

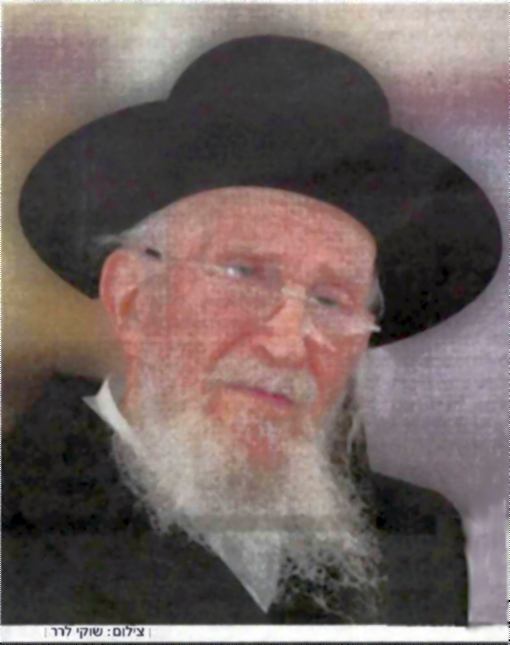

HaRav Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz, zt"l

I once paid a visit to the Gaon of Teplik, HaRav A. Polonsky zt'l who lived in a cellar in the Beis Yisroel neighborhood of Yerushalayim. Rain seeped into the apartment. The Gaon remarked that some people disguise olam hazeh luxuries, such as having a plush and spacious apartment, as kovod HaTorah.

"Some say that such things are kovod HaTorah. They equate a life of luxury with the definition of kovod HaTorah." I clearly remember how he categorically rejected such an approach: "This apartment as it is, with rain seeping in, is kovod HaTorah."

He cited the gemora (Sotah 49a) that "the tefillah of a person studying Torah mitoch hadechak, when in a state of material deprivation, is answered . . . and is satiated with the ziv haShechinah, as is written, `Your eyes shall see your teachers' (Yeshaya 30:20)."

What connection can there be between a poor person studying Torah and "Your eyes . . .."?

One who studies Torah despite suffering extreme financial difficulties does so purely lesheim Shomayim. Such a person has no personal benefits. His one and only concern is to toil over his studies, to understand and reveal its secrets and depth whose "measure is longer than the earth and broader than the sea" (Iyov 11:9). Studying in such a way, without searching for additional gain, is the study accepted by HaKodosh Boruch Hu. When one studies that way, the Shechina is with him, "For Hashem gives wisdom; out of His mouth comes knowledge and understanding" (Mishlei 2:6). He is zoche to "your eyes shall see your teachers," meaning that he gains wisdom, receiving it directly from the mouth of HaKodosh Boruch Hu as it were, and is satiated with His ziv haShechinah.

The Tur in the beginning of Hilchos Shabbos cites the gemora (Shabbos 118a), "You should make your Shabbos as a weekday so you will not need the help of others." The author of the Tur asked his father, the Rosh, if he is included among those who must make their Shabbos as a weekday so as not to need help from others, or perhaps he is permitted to ask for help since he is even unable to make his Shabbos as a weekday [i.e. he did not even have enough money for that] without help.

How strained was the Tur's financial condition! Without assistance, his Shabbos would not have been even like a regular weekday! Under such conditions, Torah mitoch hadechak, the Tur studied Torah, and Klal Yisroel was zoche to the Tur to show them the psak halocho stemming from the gemora and rishonim. This is a blessed result of Torah studied by someone who lives in poverty.

Today people have no connection to Torah mitoch hadechak. When we were young we studied Torah despite our severe poverty. We lived lives of "You shall eat bread with salt and sleep on the ground" (Ovos 6:4). Ours was a hand-to-mouth existence.

Studying Torah when in such difficult circumstances is another kind of Torah study altogether; it is a Torah study that is entirely for Hashem. The body does not exist. Only the neshomoh, the heart, and the nefesh function.

For example, every Sunday morning during the period when I studied at Yeshivas Ramailles of Vilna we did not have any bread to eat. Why? There never was a day when we bought bread directly from the bakery. A gabbai would go around from one house to another asking for bread to feed the yeshiva students. Every baal habayis would give a "note" to the grocery store authorizing the owner to allot a certain amount of bread for the yeshiva students. Armed with these notes, the gabbai would go to the grocery store and bring bread to the yeshiva. He did not put the bread in the dinning hall, but distributed a kilogram or two to each talmid. On Sunday morning, right after Shabbos, there was almost no bread to give the talmidim and each talmid had to manage by himself.

Sometimes it was even difficult to put the food in one's mouth . . . Nonetheless, we studied Torah. We suffered from unbearably cold weather with inadequate heating in our rooms. Sometimes we would wake up in the middle of the night and go to the beis midrash to warm ourselves by the oven. Other difficult material conditions existed too but we studied Torah despite them all.

There was no such luxury as tea to drink in the yeshiva. We received merely a few cubes of sugar each day. Yeshiva bochurim once discussed their suffering with the rosh yeshiva Maran HaRav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky zt'l (I believe they spoke about the lack of sugar or something else), and I was told that he answered: "Kinderlach, choshuva baalei batim in Vilna hoben dos oich nicht" (Dear children, prominent residents of Vilna do not have this either) . . . and it was no exaggeration.

At one period, R' Chaim Ozer himself would travel with another Jew by coach to request contributions from baalei batim for the yeshiva's upkeep. It once happened that R' Chaim Ozer visited a baal habayis who did not recognize him, but since the baal habayis saw a person with such a noble countenance he contributed twenty-five zlotys. After he heard that the "gabbai" to whom he contributed was none other than HaRav Chaim Ozer, the baal habayis sent an additional contribution.

The boys suffered so much that they once complained to R' Chaim Ozer of the freezing cold in the rooms. After hearing this, R' Chaim immediately sent the yeshiva a few wagonloads of fuel to stoke up the ovens. The problem was that the ovens were broken and the rooms filled up with smoke that caused the boys headaches. The result was that either they suffered from headaches or from cold — but in either case they studied Torah.

The yeshiva did not launder the students' clothing. A non- Jewish woman would come and take the dirty clothing and each boy had to finance this luxury himself. The hardship we suffered was unbelievable!

Nevertheless, no one became depressed because of these conditions. Those who were zoche to study Torah despite the grinding poverty felt that studying Torah filled their life with satisfaction and they did not feel their difficulties.

I think that today we would not be able to endure such trials since we are too spoiled. Parents spoil their children. When I was a talmid in yeshiva gedola who ever thought of buying a suit? Who thought of buying a hat? We were satisfied with whatever we had. Actually we had nothing, but we did not demand anything, and therefore did not feel the lack.

Children are educated differently today. At home children are pampered and enjoy endless luxuries. This is true even in chareidi homes. Although our generation has improved tremendously in ruchniyus and many talmidim study in yeshivos, and in general more gedolei Torah emerge from the yeshivos, the gedolei Torah of that age were different.

For example: On an erev Shabbos afternoon I went to look for a room to rent in Vilna. I knocked at one home and a bochur wearing a large yarmulke (initially I was not aware that he was a bochur) sat at a table overflowing with seforim. Later I found out that he was R' Itzeleh of Vilna.

(There were two R' Itzelehs in Mir: one was R' Itzeleh of Vilna and the other R' Itzeleh of Charakover. Later R' Itzeleh of Vilna became the son-in-law of HaRav Yechiel Michel Gordon zt'l and served as a rosh yeshiva in Lomzha Yeshiva in chutz la'aretz. Those were two eminent bochurim of that time.)

Nowadays we do not have such bochurim. Our present concepts of gadlus, greatness in Torah, have diminished; we have other concepts of gadlus.

But also in these times when Torah mitoch hadechak is missing, it is still possible to study Torah in a way that will resemble Torah mitoch hadechak. What is vital is that a person not hold material matters in high regard. When Torah study is a person's main aim in life, when he aspires to enjoy his Torah study, this is similar to studying Torah mitoch hadechak.

Modern society offers a wealth of pleasures. Society promotes indulging in pleasures, enjoying oneself, and satisfying one's desires. A person must work hard to uproot the impression of what he sees, so that material matters will not be his main objective in life. In America there is a popular expression: tzu machen a leben (to have a great time). This can be done in several ways, either by looking for only the best and tastiest food, roaming around candy stores and restaurants, running after the last fashion: buying a suit, a hat, or a yarmulke of the latest style. Such a life is one of studying Torah while also enjoying oneself and fulfilling one's desires. Divrei Torah will not remain, writes the Rambam, by someone who lives like that.

It is necessary to discuss these topics at length. Not to indulge in pleasures is a forgotten concept. People just do not understand what that is! One does not recollect that all material matters are only of secondary importance and the most important value in life is ruchniyus. The Midrash Tehillim teaches us on the posuk, "The tzaddik eats to satisfy his soul" (Mishlei 13:25), that a tzaddik eats merely a little to sustain himself for avodas Hashem. Although he dresses cleanly and eats all he needs, he does all this only to sustain himself. On the other hand, the rosho and the fool eat for their own enjoyment, to fill their bellies, and do not care how much it costs them.

The gemora in Chulin (91a) tells us that Yaakov Ovinu returned to Nachal Yabok to fetch his small pots since tzaddikim are careful not to forfeit their material possessions even when they are worth only a prutoh. A kosher prutoh is difficult to come by!

Does anyone in this day and age have such concepts? We are accustomed to squandering money and being pampered, which of course necessitates having much money. People chase after money and are preoccupied in searching for it high and low and devising various plans to attain it. Under such conditions can one possibly be engrossed in Torah study?

One becomes terribly confused. If not for this decline in understanding and perception of the value of life that we see today, many more talmidei chachomim would become gedolei Torah. They do not emerge gedolei Torah because material luxuries and pleasures disturb their laboring over Torah.

I heard a story from the Ponovezher Rov zt'l about the Chofetz Chaim. When the Rov studied in Radin, the town of the Chofetz Chaim's yeshiva, he once needed to look up a matter in a certain sefer. Since the Rov was a frequent visitor at the Chofetz Chaim's house, almost a family member, he remembered once seeing the Chofetz Chaim looking in that particular sefer.

The Rov went to the Chofetz Chaim's house and asked permission to look some matter up in that sefer. The Chofetz Chaim answered that he only had borrowed the sefer and had already returned it. Afterward the Chofetz Chaim turned to the bookshelves and began thinking about what he had just said. "These are my seforim. They became mine because I bought them. With what did I buy them? With money. I exerted myself and with the money I received for my efforts I bought these seforim. Money is exerting oneself. One's efforts take time. What is time? Life! For seforim I gave part of my life!"

This is the real hashkofo of how to value life. We must realize what is our main objective in life and what is secondary. It is difficult to talk about such topics since at present all aspects of establishing oneself in life are defined as being unquestionable necessities.

When we want to define the greatness of an odom godol we sometimes say he was a talmid of a certain godol beTorah. We all know that today only a few truly deserve the honor of being called talmidim.

Rabbeinu R' Chaim of Volozhin zt'l was considered a talmid of the Vilna Gaon. Our history is replete with other such examples, such as talmidim of the Chasam Sofer, and HaRav Elchonon Wassermann zt'l, who was a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim. In Chazal we find that some tannoim and amoraim were classified as being talmidim of a certain godol beTorah. Actually the entire transmission of Torah from one generation to the next is according to the tradition handed down to us from Moshe Rabbeinu a'h, from a constant chain of a rav giving over the Torah to a talmid.

Similarly, the method of understanding the Oral Torah, how to analyze the give-and-take of the sugya until the psak halocho, must be according to our tradition as taught to us by our Torah mentors. Each generation must study according to the manner understood from its mentors.

We know that in the period after the Talmud was finished, the rishonim were talmidim of the geonim. Throughout our history, yeshivos existed in Klal Yisroel to continue teaching and transmitting Torah to their talmidim according to the kabolo they had received, until our latest period, the period of the roshei yeshivos.

I heard from a talmid of HaRav Boruch Ber Leibowitz zt'l, the rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Kamenitz, that he once remarked to an acquaintance, another godol beTorah, that it is now our duty to produce talmidim who can continue teaching Torah to the future Jewish Nation. He emphasized that this is a part of "studying Torah for its own sake" to which each one of us is required to aspire.

Because of this feeling our mentors dedicated themselves to produce talmidim and bring them nearer to Torah.

When I studied with the Rebbe zt'l in Vilna (the gaon HaRav Shlomo Heiman zt'l who was later a rosh yeshiva in Yeshivas Torah Vodaas in Brooklyn) we saw in him an exceptional image of a Jew from whom the sweetness of the Torah radiated. This sweetness brought each one of us nearer to studying Torah. HaRav Heiman exemplified how to forge relationships with talmidim, and would speak to each one of them as if to a prominent person. We never heard from him any criticism about a talmid and if a talmid offered a piece of unsound reasoning, he would correct him in such a way that the talmid would not even realize he was being corrected. For example, he would review what was said and say: "This and this is how the talmid explained." This despite the fact that the talmid himself did not intend to say that. The Rebbe weighed each word. I remember that at the time the bochurim did not have food because the yeshiva was poverty-stricken, the Rebbe would also fast even though he had food at home.

We also saw by HaRav Isser Zalman Meltzer zt'l, the father-in-law of HaRav Aharon Kotler zt'l, a special relationship to each talmid. We felt his sincere love and extraordinary satisfaction from us. For example, when he would say a public shiur and one of the audience would comment that we can understand the pshat of Tosafos in such and such a way . . . HaRav Meltzer would value it immensely if it was true and based on acceptable reasoning. He would stop the shiur many times and would emphasize: "That talmid made a good comment, a true comment." Even when he would later finish the shiur and would be at the front door ready to leave he would again review what that talmid had said. When he needed a sefer from the bookshelf he would rise eagerly and fetch it himself.

End of Part I

HaRav Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz was the rosh yeshiva of the Yeshiva LeTze'irim of Yeshivas Ponovezh in Bnei Brak and a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Degel HaTorah.