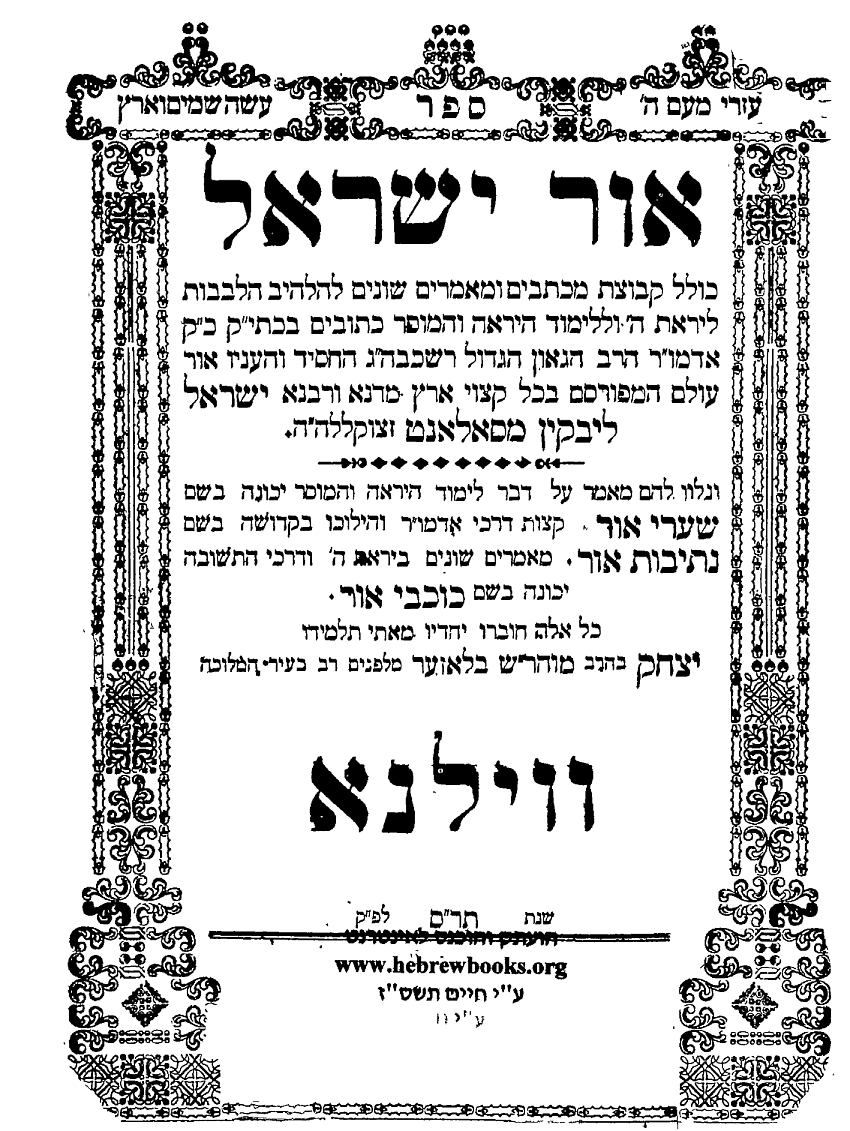

Front page of the Sefer Or Yisroel

We originally published this in 1995, about 24 years ago. Written by the founder of the Mussar movement, it provides basic insight and guidance into learning Mussar all year — and especially in Elul. This is always timely and important.

Part I

HaRav Shlomo Wolbe once said, "It is almost impossible to do teshuva without being familiar with these letters in Or Yisroel (7 & 8)." We are happy to be able to present Letter 7 here in translation, along with some other selections. Readers are advised that the material is dense and difficult, and it requires attentive and serious study.

HaRav Uri Weissblum in the introduction to his annotated version of Or Yisroel makes the following comments about the importance of mussar study in our days.

There has arguably never been a generation so much in need of mussar study as ours. If we consider what is happening around the world today, we notice that all inhibitions and conventions have been breached. Something which was always assumed to be bad is now defined as good and vice versa.

The worst deterioration has taken place in the field of interpersonal relations. There is almost no aspect of bein odom lechavero in which the most basic foundations of moral behavior have not been affected.

The immense technological progress of recent times and its effect on all spheres of life has also left an imprint on modern man. The media intrude upon us wherever we go. Man has stopped thinking. The newspapers think for him and mold his personality. The microchip revolution has enabled the various media to transmit information instantly, and this has widened the gulf between different groups. All of life's events are absorbed via the camera lens, without the eye being given a chance to experience and be moved directly by the event.

The cacophony of sounds emitting from electronic instruments, that attacks us wherever we go, has robbed us of the ability to appreciate the wonder of sound. The telephone is replacing personal contact. Medicine has become just another subject for research.

Curing the sick is no longer the main concern of the medical man. Instead the emphasis is put on producing the correct diagnosis and expanding the horizons of our knowledge. When human life is held cheap, mistaken diagnoses abound: man, being surrounded by machines, has himself turned into one.

There can be no doubt that all of these negative influences have left their mark on the Torah world too. Our feelings have become dulled. We are no longer accustomed to tsnius in our avodas Hashem.

We have almost forgotten what it means to invest mitzvos with the requisite thought and intentions and what the true nature of yir'a is. Even when we feel an urge to come closer to avodas Hashem, we do not know how to go about this, and our improvements are therefore restricted to externals. Interpersonal relations among Torah-true Jews in the modern age leave much to be desired.

Moreover, the wonderful phenomenon of thousands upon thousands of baalei teshuva who crave perfection in their kiyum haTorah umitzvos, requires that we make every effort to elevate ourselves.

The appropriate response to this situation is to return to an intensive study of works dealing with mussar. Someone who applies himself to study of this kind will gain access to worlds that were hitherto totally hidden from him. The study of mussar has an effect that may be compared to a telescope bringing distant worlds into focus. It also works as a microscope discerning whole worlds within tiny points, which man comes across constantly without realizing it, whether it be behavior bein odom laMokom or bein odom lechavero. These worlds remain concealed for want of suitable tools to identify and experience them.

Following are three letters by R' Yisroel Salanter which all talk about inyonei deyoma.

Letter 7

Everything has a cause and an effect. The gathering-in of the produce from the field is preceded by many causes: sowing, plowing and so on. The acquisition of wealth has its own causes, such as the pursuit of trade. Every cause is, at the same time, an effect of a preceding cause. The seed in the field is the immediate cause of the crop's growth, and is in itself the result of a man's having sown the field. This latter act is the effect of the man's desire for a harvest or for the income which will result from his sowing. This is the principle: there is no effect without a prior cause, and there is no cause that is not itself the result of a further cause, leading to the Prime Cause, which is Divine and which is a full cause unto itself.

In the pursuit of man's physical needs (such as the acquisition of wealth) and of his abstract needs (such as the desire for honor), the prime cause appears, to a superficial observer, to be man's will (although in reality everything stems from the true Prime Cause) which appears to arise on its own. Man's will in turn gives rise to effects which become causes for further effects until the original wish is actualized. A person's wish may also derive from another person ("B"), who persuades or forces him ("A") to have such a wish or intention. In such a situation, "B" has, for his own reasons, sparked off for "A" something which appears (to the superficial analyst) to be a prime cause.

Let us now apply these principles to our subject matter: what is the prime cause that encourages us to reflect on our deeds and to study mussar during the month of Elul? (The same question arises during the rest of the year, as far as our service of HaKodosh Boruch Hu is concerned.)

After all, spiritual matters are unlike material matters, in that man has no natural urge to satisfy his spiritual needs. Chazal were concerned about this and — relying on Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer (46) — instituted the blowing of the shofar during Elul. The shofar became the prime cause that served to awaken man from his slumber and from the vacuousness of his mundane occupations and to cause him to reflect on his deeds. As the prophet says, "Shall the horn be blown in a city and the people not tremble?"

*

It is well-known that an effect cannot result except from a cause that is similar to it. An important, difficult effect will not result from a trivial cause.

The blowing of the shofar was a sufficient prime cause for someone who is wholly immersed in avodas Hashem, who had no need of anything more than a slight push to arouse him to engage in serious introspection.

However, what can we say? What are we to do? We, are totally involved in our everyday affairs, and our hearts are hard as the hardest stone. Can a slight awakening [such as the shofar] make an impression in our hearts of stone?

Still, if we see things clearly and do not become ensnared in the webs of the yetzer hora, if we do not turn light into darkness nor say that the slight is heavy — then we can see how it works.

It is very easy to go once in a while to a place where mussar is studied during Elul. With all our toil there is a time free of distraction whether in the day or the night when we can study mussar. The blowing of the shofar is thus strong enough to arouse us to study mussar. In turn this study can be a powerful cause capable of further important and significant effects.

*

This is how Chazal have expressed themselves: "If this wretch [the yetzer hora] attacks you, drag him to the Beis Hamedrash" (Kiddushin 40). There are different Batei Medrash for different purposes. In one, people may study matters of proper conduct of business. Another deals with eating kosher food, and so on.

Thus the remedial qualities of Torah in overcoming the yetzer [that are found in the Beis Medrash] are on a general as well as a particular level. On the general level,

it is told in the name of Rovo that "while one is engaged in (the study of) Torah, it protects and rescues" (Sotah 21a). On the particular level — and this is the foremost and almost the main thing — every topic has its own particular cure within the Torah.

For example, if the yetzer is giving you trouble in matters of business, you must drag it to a beis hamedrash where the relevant parts of Torah are studied; if your tongue is the culprit, then you must study the laws of loshon hora. Thus a person must ascertain which parts of the Torah the wretch is attacking, and drag it to a beis hamedrash in which those parts are studied.

*

For this purpose, it is vital to study mussar, especially during Elul, for two reasons.

First, there is the physical aspect, that each man and his family are in great physical danger. When the shofar is blown on Rosh Hashana, it is a time of great judgment, when man's deeds are recalled and he is judged. At that time, each person is comparable to the Kohen godol when he went into the Kodesh Hakodoshim. As Chazal say in Rosh Hashana, 26a [that even though the shofar is used in the outer precincts of the Beis Hamikdash], "since its purpose is for zikoron it is as if it were [taking place] within [the Holy of Holies]" (see Rashi ibid.).

A man who loves himself and his family who are dependent upon him, fearing for the future, would do his utmost to improve his ways, or at least to humble himself and make himself poor in spirit, which is the key protection from the imminent danger of the judgment. (Even though we see that many are judged for life even without preparations and arousal of yir'a and mussar.) As Chazal say, "Every year that is poor (Rashi: `when Israel humble themselves') at its opening, becomes rich before it ends" (Rosh Hashana 16b), and also: "On Rosh Hashana the more a man humbles himself, the better [is his prayer]" (ibid., 26b).

"To everything there is a season... (Koheles 3) and man knows not his time; as the fish that are taken suddenly in an evil net...even so are the sons of men snared in an evil time, when it falls suddenly upon them," (Koheles 9) without any time to prepare a shield to protect himself from the danger of the awesome Day of Judgment [after death]. Everyone can see that almost every Rosh Hashana, young men are sentenced to death Rachmono litzlan, while others of the same age are saved. HaKodosh Boruch Hu is long-suffering, until each individual's allotted time arrives. Every person has his own fixed time.

Using the imagination can be very effective in achieving mussar's ends. A person should picture himself as the Kohen godol and he had to enter the Kodesh Hakodoshim on Yom Kippur. How anxious he would be lest he should come to any harm choliloh! He should similarly strengthen his emunas chachomim, since they invalidated the use of a shofar made out of a cow's horn, because "an accuser (the cow is an "accuser," because it was worshiped as the Golden Calf) may not act as defender [i.e. used as a shofar]" (Rosh Hashana 26a).

Thus, although it is permitted to wear gold in a sanctified synagogue (but not in the Kodesh Hakodoshim, since it is also an accuser as indicated also in the same gemora), a shofar, since its purpose is for zikoron, is also subject to the same limitation [even in the synagogue]. That is to say, since the shofar comes for zikoron, and man is then held to account for all his deeds, it is a situation comparable to that of the Kohen godol entering into the Kodesh Hakodoshim. Anyone who analyses this matter in depth, cannot help but be very afraid.