NEWS

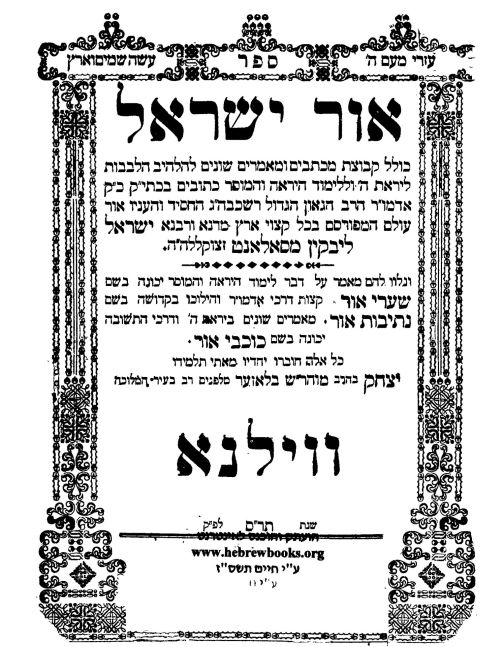

Mussar Study Before The Yomim Noraim — Letters From Or Yisroel

by HaRav Yisroel Salanter zt"l

HaRav Shlomo Wolbe once said, "It is almost impossible to do teshuva without being familiar with these letters in Or Yisroel (7 & 8)." We are happy to be able to present Letter 7 here in translation, along with some other selections. Readers are advised that the material is dense and difficult, and it requires attentive and serious study.

This is the end of the first letter and the other two.

Every year the prime cause for self improvement is the fear of every believing person that he will come to a bitter end if he abandons Torah and mitzvos. However, our desires overpower us. One should get used to studying poskim (although one should not stop attending one's regular shiurim, for "a synagogue should not be demolished" (Bava Basra, 3b)).

When one comes across a din that is relevant to him, he should study its sources, and delve into the matter deeply in accordance with his intellectual capabilities. Study of this kind will leave almost as big an impression on his soul to fulfill that din as reflection on the fear of G-d.

Still, such reflection on yir'a should not be neglected. "If there is no Torah, there is no fear of G-d, and where there is no fear of G-d, there is no Torah" (Ovos). �

Those who are sick with despair about their ability to overcome their overwhelming desires — and despair is indeed a serious disease — must realize that every sin possesses various aspects. There are aspects that one generally finds difficult to avoid, but there may be aspects even of the same sine that are easier, especially at various times.

For example, the sin of bitul Torah is very different on a weekday which is a time of distraction from on Shabbos, a time of freedom from distraction. The situation with regard to learning Torah is different when your mind is unsettled from when nothing troubles your mind.

Similarly with all details of aveiros. Each aveira is analyzable into different aspects dependent on the situation person and on his innate abilities. Not every time is the same and not all abilities are the same. The easier a man finds it to refrain from sinning, the greater will be his punishment for not doing so, as Chazal said in Menochos (43b): "Greater is the punishment for the [nonobservance of] the white threads [of tsitsis] than for [the nonobservance of] the blue threads."

We should make it a habit to fulfill the verse in Mishlei, "If you seek her as silver..." Consider our bodily needs, and compare how we relate to the requirements of our soul.

A man works hard even for only a small remuneration. When we are sick and in severe pain, we do not find it difficult to try to alleviate our suffering.

Why, then, do we not act similarly with regard to our soul? We should at least keep those mitzvos that are easy to fulfill, and keep away from those aspects of sins that we find easy to avoid. Doing this will save us from severe suffering Rachmono litzlan.

There should be no room for despair if we use our behavior regarding bodily needs as a model for our conduct in spiritual matters. We must strive to encourage our desire to fulfill the mitzvos in their entirety, including learning Torah, and one should always strive to avoid all sins.

During the month of Elul, even though there is not much time, we should learn a short sefer, such as Rabbeinu Yonah's Sha'arei Teshuva, which speaks about almost all the mitzvos and aveiros. When we come across a topic there that is especially relevant to our personal situation, we should study it in depth, each person according to his capabilities and the time available to him. The different aspects of each sin mentioned above should also be borne in mind when studying such texts.

This way it may be hoped that on Yom Kippur we will become complete baalei teshuva on at least one of the aspects of the aveira, making a firm resolution to abandon at least one particular easy aspect of that particular sin. Even such an action on our part will yield immense results in this world and the next.

We see in practice that a person finds it easy to perform an act that is almost like "second nature" to him, even though he may later find it difficult. Examples differ from place to place. In this country people find it easy to keep Shabbos, whereas in Germany it can almost be said that being a shomer Shabbos is more difficult than any other aspect of avodas Hashem.

Studying in depth makes such a powerful impression on the soul that the material you have studied becomes internalized and you find yourself fulfilling the mitzva virtually without the aid of mussar study, and you will be able to withstand tests. Studying Torah in depth with regard to the dinim that are critical to you, is the best way to ensure that you will observe them properly.

=====

Letter 15

The essence of the days of repentance is the resolution to abandon the cheit. This is the most difficult part of our avoda on Yom Kippur. The most severe of all sins is theft — even if there is a bin full of sins, gezel is the first to accuse us.

We must at least do teshuva for those sins that are especially serious. This may be measured according to the subject and the object of the transgression.

The subject that is most serious are those acts of sin that could most easily have been avoided by the transgressor. The punishment for these is greater, as Chazal say in Menochos, "Greater is the punishment for [the nonobservance of] the white threads than for [the nonobservance of] the blue threads." The object that is most severe refers to a case when the victim, was [for example] a poor person. Then the sinner's punishment is proportionately more severe.

How hard it is to find a way to do this. ... How good it is to have the opportunity to correct the sin of a possibility (chashash) of theft, where the subject is easy (when it is not difficult to avoid the theft) and the object may be most severe. ...

The principle holds good for other sins too. Bitul Torah, for example, which, as the Sha'arei Teshuva quotes in the name of the Sifrei, is the most serious of all sins, varies in severity according to subject and object. The most severe aspect of this great sin according to the subject (the person) is whenever the circumstances are conducive to learning, either because of the time (e.g. on Shabbos) or because he has a lot of spare time, then the punishment is greater.

According to the object the most severe punishment is for failing to study those topics that are essential to know, either for the purpose of knowing oneself what to do or in order to know when to ask someone greater how to act. A person is punished for his every sinful act or omission, but the easier it is for him to the act properly, the harsher will be the punishment for not doing so.

We must find a way of resolving resolutely to keep at least those aspects of Torah and mitzvos that we find easy to observe. This way we can attain teshuva for the greater part of our sins, because sins are not measured simply by their number ("the quantity"), for the severity of each sinful act ("the quality") is also taken into account (see Rambam, Hilchos Teshuva, chapter 3). The commission of one sin which we could easily have avoided is considered more serious than the commission of many sins that are harder to keep.

The same applies within each individual sin: transgressing even a minor aspect that we could have avoided with only a small effort is more serious and is more severely punished than the transgression of many other aspects of the same sin the abstention from which require much effort on the part of the sinner.

Regarding limud Torah, it must be realized that even someone with a very short memory could easily repeat in his mind what he has learnt, thinking the material over slowly in his mother tongue. When walking in the market (in a clean place), or sitting in a wagon, or even in the middle of other activities, he can mull over the content of the gemora which he is learning, even without remembering exactly what each individual tanna and amora said.

A businessman should actually find it easier to do this than someone who is learning full-time, because the latter does not have the time to go over what he has learnt by heart, lest he be distracted from his main studies. The businessman, on the other hand, has plenty of spare time during his day to review the daf.

Those of us who are busy should make the most of this wonderful opportunity. It is easy to do in theory, and we should see to it that we do it in practice. Let us not yield to the blandishments of the yetzer who argues that it is difficult!

Slowly but surely he can learn the content of the Torah by heart in his mother tongue, even if he has a very bad memory, especially if he is very busy, because such a person can find the time to go over what he has learnt in his mind.

It is very helpful in this respect to learn mussar books that talk about the gravity of the sin of bitul Torah, in order to strengthen one's resolve not to let any extended period of time pass without studying Torah, which is the foundation of our lives. (Written the night of 8 Tishrei, 5637)

Letter 16

"`Remember also your creator in the days of your youth before the evil days come' — this refers to the days of old age (Shabbos 151b)."

My ideas are disjointed. I find it difficult concentrate enough to answer a difficult question: how do we destroy the yetzer, which we are duty bound to fight? Although there is no clear-cut strategy for fighting him, and there is no guarantee that any specific method will be successful at any particular time, there are days (the aseres yemei teshuva) regarding which the poskim have ruled that it is obligatory to study mussar books, for during this time we are preparing to stand in judgment, at the conclusion of which we will know whether we are to live or, chas vesholom, do not.

A servant wishing to plead with his master appeases him with a humble spirit. Hashem does not reject such a supplication. The humble spirit arises within man as a result of intensive study of mussar works, during which one's soul is poured out to Hashem yisborach Shemo.

If you indeed study mussar, and thereby animate your soul, then the impressions of this study will remain with you even after the Days of Judgment, and you will have a strong desire to continue studying throughout the year. (From your friend who blesses you that you have a good year.)

Something that carries within it much of the element of fire, since, just as a fire may not be evident, but a small spark can start a great conflagration. Similarly, although I am not capable in my present state of dwelling upon these matters at any great length, my hope is that these few words will remind you of what I wrote to you recently and no doubt those things have entered deep into your hearts.

I wrote that you should go to the beis hamussar, especially during the aseres yemei teshuva and there learn mussar with hispa'alus hanefesh.

Prayer, too, preferably with a minyan (see Taanis 8), leads to a great spiritual awakening, which can overcome all obstacles.

|