| | Feature

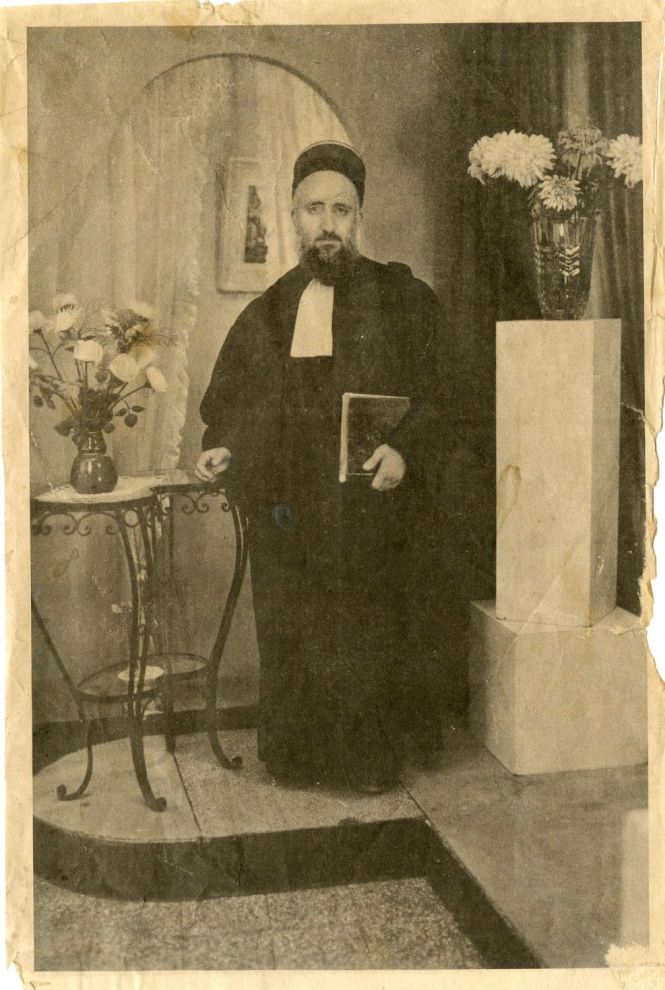

The Gaon, R' Matzliach Mazuz, Hy"d: His Fifty-Fourth Yahrtzeit

by A. Avraham

This article was originally published in 1996.

His Torah Lives Forever

R' Matzliach was raised on the knees of the great sages of Tunis, and from them he imbibed his ability to toil in Torah, his perspicacity and his vast Torah knowledge.

As a youth, he studied with amazing diligence. Even then, the remarkable traits of perfection and precision were evident in him. He would spend his nights in the bais medrash, surrounded by sacred seforim over which he would pore until dawn. Then he would proceed to the local synagogue, and pray with the first minyan. Even then, he was careful to pray with the netz.

It was his adherence to so rigid a schedule which caused him, as a youth, to long for a watch — a costly item during those days. When he finally received one, he used it to his plan his day: a part for praying, a part for sleeping, a part for eating, and the majority of the time for Torah study.

By the age of sixteen, he had already written responsa, which in their style and length were like those of venerable scholars. One time, his mentor asked him to write an essay on the mitzvah of fulfilling a deceased person's last will and testament. Two weeks passed, and R' Matzliach still hadn't returned a reply. His mentor asked: "What is taking so long? The whole answer shouldn't occupy more than four or five pages." R' Matzliach then showed his rav a number of the pages he had written, and said that he still hadn't competed his answer.

In the end, he wrote about three hundred pages, saying: "I still have two hundred more to go."

On the day of his cousin's wedding, he was faced by a dilemma. On the one hand, he had to be present. On other hand, he had many deep sugyos which he still had to probe. How did he resolve the problem?

While seated at the wedding repast, he mentally probed those sugyos. Every now and then, he would be seen entering a side room for a while, and then emerging. In that room, he would quickly write down the thoughts that had entered his mind. Every moment was precious to him.

At the age of eighteen, he married his cousin. On the afternoon prior to his wedding, he disappeared, and no one knew where he was. His relatives searched for him, but to no avail. At last his mentor was consulted, and he said: "You will probably find him in the otzar seforim of the R' Eliezer Synagogue (his permanent place of study). And indeed, there he was!

His family wanted to take him home to prepare for the wedding. But he told them: "I have already bathed and dressed. I am ready for the chuppah. As soon as you call me, I will come. It's a pity on the time being wasted."

He later earned his living as a watchmaker, and utilized his every free moment for Torah study. During that period, he wrote many novella, and it was obvious that he was deeply engrossed in learning, despite the fact that he had to ply a trade.

In his heart, too, he disdained worldly wisdom, and would constantly say: "Understanding the true meaning of Rashi on one verse of the Torah is worth all of the chochmos of the world."

The interior of the main shul in Djerba

Getting the Truth

When he became a dayan, he saw that the three years during which he had plied his trade, had taught him practical lessons on human nature and its wiles. He pointed to the words of the Gra (in Adderes Eliyahu, parshas Shofetim) which state that a dayan must excel in two things. He must be well versed in all parts of the Torah, and he must understand the wiles of people, so that he will be able to arrive at the truth. And indeed, he was an expert in investigating clever lawyers and plaintiffs of all sorts. From his investigations, the truth would always surface, like oil atop water.

One of the rules he followed when investigating plaintiffs was not to ask them pertinent questions one after the other, but rather to insert insignificant questions which had very little to do with the case at hand, between the important ones. He knew that the lawyers had surely instructed their clients to make some false claims. By diverting the focal point of the questions, the plaintiffs generally forget their claims. When caught off guard, they would quite incidentally reveal the truth.

One time, a plaintiff, who knew that he was guilty, appeared before R' Mazuz with a clever lawyer who had taught him how to lie. They reviewed their claims before coming to the court, and were certain that they would emerge victorious.

The lawyer presented his claims to the dayan. Then the plaintiff was called for a cross examination. As was his custom, the rav began to speak at length. He asked many questions, until the plaintiff was put at ease. He told R' Mazuz that he had known him for many years, and planned to write a biography about him. The discussion became intimate, and the two spoke to each other like friends.

Suddenly R' Matzliach threw in the main and decisive question. The man blurted out what was uppermost on his mind at that time, and forgot what the lawyer had instructed him. No one in the court noticed what was occurring, accept the lawyer. He tapped himself on his head and said: "All that we planned has been turned upside down."

Later on, at the end of the deliberation, the lawyer said: "If the case hadn't been judged by R' Mazuz, my client never would have been incriminated."

When he became thirteen, his father bought him a pair of Rashi tefillin. However, he also wanted Rabbenu Tam tefillin, and began to save up his own money until he had thirteen francs, the cost of a pair of tefillin in those days. Then he went to a expert sofer, and asked him to prepare the most mehudar Rabbenu Tam tefillin for him. He then warned him not to tell any one about this matter, lest people suspect him of being presumptuous.

His strong character enabled him to control his inclinations in a remarkable manner. His students, who had known him from their youth, relate that they had never seen him drinking cold water, not even in the heat of summer. While all of his friends would bring jugs of water to the bais medrash, he would be satisfied with simple water from the faucet.

He behaved this way, not because he had abstained from drinking cold water, but because he wished to teach his students not to be enslaved by their desires. At home, far from he eyes of his students, he would drink cold water every now and then.

The Zarzis shul in Tunisia

R' Matzliach was childless for many years. One time, the pious darshan, R' Yaakov Ankari appeared in R' Matzliach's bais medrash. During shacharis, he asked him: "Why don't you bring your children to the synagogue to hear tefillah betzibbur and to answer Amen, and he replied: "I still haven't merited children."

Hearing this, the darshan jumped up, clutched his tefillin shel rosh with his hands, and said, "Next year your wife will give birth."

And so it was. On the 23rd of Cheshvan 5697, his first child was born. He was named Tzemach Bracha Yehuda. The child was raised on the banks of Torah and avoda, but sadly did not live long. He died on Purim 5705, when he was only eight years old.

A few days prior to the death, R' Matzliach had a dream, in which he saw himself standing before the Heavenly tribunal, and studying the fate of his father-in-law, R' Menachem Mazuz, who was also his uncle, as well as the fate of his son Tzemach. The verdict he issued was: "Menachem is not guilty and Tzemach is culpable." Then he awoke.

A few days later, when his dream materialized, he cried bitterly. "Why didn't I protest the verdict in my dream," he asked himself in pain. But the past cannot be restored, and his son died, while his father-in-law lived for a few more years. He was particularly grieved by the fact that the saintly R' Yaakov Ankari had not included the words "ben shel kayama" (a son who will live) in his blessing.

This story, which made a deep impression on his students, availed one of them later on. A few years after Rabbenu's death, that student, who had been married for eight years, still had no children. In his dream his saw his mentor and asked him to bless him with children."

But R' Mazuz replied: "Because you have left your Torah studies, I am not willing to help you."

The student pleaded: "I promise to return to learn."

R' Mazuz answered: "If so, then I promise you a son this year."

After seeing his mentor leaving, in the dream, he recalled the above mentioned story, and ran after him, pleading with him to include the words, zera shel kayama in his blessing. "Yes," replied R' Mazuz, "ben zachar shel kayama." The student awoke, and returned to his Torah studies. That very year a son was born to him, and later on a daughter.

One of R' Mazuz's students relates: "A student once came to Tunis from a nearby city, in order to study under Rabbenu. He stayed with one of his relatives near the yeshiva, and during the holidays would return home. The student was only twelve years old, however, he was the best student in his class, and was transferred to a higher one. He would borrow books from the yeshiva's otzar seforim, and study in his apartment at night.

"During the shiur, he would make genuine chidushim and ask valid questions, which were so clever that R' Mazuz actually published them in a pamphlet which he named after the student, in order to inspire him to grow in Torah. One time, before the holiday vacation, the student was seen returning the books he had used to the yeshiva. At that moment, Rabbenu realized that all of the youth's chidushim had been stolen from those commentaries.

R' Mazuz, who was very angry at the student, changed the title page of the kuntrus named in honor of that student, stamping it with the acronym: chana"s (chet, nun, samech) — to stand for the words, chamor nosai seforim — a book-bearing donkey.

When the student returned to the yeshiva, his situation deteriorated, until one day, Rabbenu grew angry at him and told him to leave the yeshiva.

The friend who related this story asked Rabbenu: "Rebbi, how is it possible that you have cast off your beloved student in one day? Why not rehabilitate him?"

To this, Rabbenu replied: "You have yet to see what will become of him. I know that he is incorrigible."

These words pierced the heart of the young man's friend like arrows, and years later, when the two were living in Eretz Yisroel, he looked up his friend and discovered that he had been convicted of a serious crime. In his Ruach hakodesh, Rabbenu had foreseen the young man's destiny.

HaRav Meir Mazuz, son of HaRav Matzliach and current rosh yeshiva of the Keser Rachamim yeshiva in Bnei Brak

Precision and Care in Word and Deed

One of the most outstanding aspects of Rabbenu's many faceted personality was his meticulous writing and speech. One time his son marked down in the margins of Shaar Hamelech: See Mishnah leMelech, Chapter Thirteen of Shgaggos. His handwriting was nearly the same as his father's.

When Rabbenu opened the book at a later date, he first assumed that this remark had been his own. After looking at it again, though, he said: "No it isn't mine. I wouldn't have written "Chapter Thirteen of Shgaggos," but "Chapter Thirteen of the Laws of Shgaggos." Such was his precision!

He was very careful to articulate the words of his prayers and to read the Torah clearly, pronouncing every single word. When he spoke, he observed all the laws of grammar of loshon hakodesh mentioned in the book, Lechem Bikkurim.

He learned the laws of Torah reading while in the synagogue, Zera Yitzchok, where he had read the Torah when he was young. R' Zerach and R' Yonah Teib, who were well versed in grammar and taamim prayed in that synagogue. R' Zerach noticed Rabbenu's excellent character traits, which were particularly evident during that period, when the overall situation the youth of Tunis was at an ebb. He sat beside him during the Torah reading for an entire year and taught him all of the finer aspects of the taamim, which he had learned from his own mentors.

He would read the verse "Vayehi bishkon Yisroel, in parshas Vayishlachtwice, once according to the regularly used taamim, and another time according to other taamim, brought in the books Minchas Shai and Lechem Bikkurim.

He would recite all of his prayers, too, in accordance with the laws of Hebrew grammar and the foundations of the Kabalah. He passed on a number of his practices to his students. He instructed his students not to pause after the words: "vehosheiv es ha'avoda ledvir baisecha" in the Retzai blessing of the Shemoneh Esrei, but to continue directly on to ve'ishai Yisroel, because the letters "yod-aleph of the words ve'ishai Yisroel are linked to the preceding part of the verse.

He showed his students an excerpt from the Beis Yosef, part one, stanza 142 which says in the name of the Orchos Chaim, that it is an ancient custom to recite "Vehu rachum yechaper ovon" after the Torah reading, in order to atone for errors made when reading the Torah.

He once told his son, that he was prompted to be so careful about his pronunciation of the words of the prayers after one of his students had told him how a teacher of French would train his students to recite the letter "u" properly, and that when one would exchange it with the letter "e" the teacher would make a special effort to train him to recite it properly.

Rabbenu drew a kal vochomer from this story, saying: "If in mundane matters, such as the pronunciation of a French letter, people are so meticulous, how careful must we be to properly articulate the words of the prayers we recite before the King of Kings HaKadosh Boruch Hu."

From that day on, he began to be very meticulous about his pronunciation, and would always be the last one to complete his prayers. He behaved this way for three years, until the correct pronunciation had become second nature to him.

Leading Up to His Petirah

A month prior to his death, his father, the author of Kisei Rachamim appeared to him in a dream. He grabbed him and showed him a beautiful hall and said to him : "My son, this is where you will sit in Gan Eden. He told the dream to his brother-in-law, R' Ankari, joyously saying: "Here, I live a life of penury. But I have just been shown my place in the World to Come."

On Motzei Shabbos, parshas Shemos of the last year of his life, his students arrived in his home for Havdalah. After Havdalah he strengthened his students with words of Torah and mussar. He explained the words of the mishna in Pirkei Avos: "Do not yearn for the tables of kings," and asked:

"Why should a commoner yearn for the tables of kings? A hero is jealous of other heroes, a wise man of other wise men. But the Tanna is comforting us and saying: Do not regret your difficult situation, Do not regret that your table is less than those of other talmidei chachamim (who are called kings), because your table in the World of Truth is greater than theirs. In the end, when a true accounting is made, those things which we enjoyed in this world, are deleted from our credits in the World to Come." Then, to the amazement of his students, he dwelt at length about the World of Truth.

On morning Monday of the week of parshas Va'eira, the 21st of Teves, he felt ill. His wife pleaded with him to remain home, but he refused, because he knew that the vosikin minyan required his presence. Before the netz, he was already in the synagogue.

After the prayer service he studied Chok leYisrael, as was his custom. The words which he studied at that time were those of the Zohar which say that the reward of one who observes Hashem's mitzvos and studies Torah day and night is reserved for the World to Come. A few moments later, he was shot by an Arab.

His Tragic End

It was the 21st of Teves, 5731, that three gunshots pierced the air of the Tunisian city of Tunis, killing the gaon, R' Matzliach Mazuz Hy"d, while he was wrapped in his tallis and tefillin. The hands of a degenerate Arab committed this criminal deed, causing not only one person's blood to flow like water, but the blood of the entire Jewish Nation.

A seven year old Jewish child was the sole witness to the murder. He related that the Rav had lifted him up and had spoken with him in Torah.

That day was also the 18th of January, which marked the liberation of the republic in Tunis, and very few people were in the streets. From a distance of fifty meters, the Arab fired his gun and hit R' Mazuz in the leg. R' Mazuz fled to a side alley, and began to shout, hoping that someone would come to his aid. While he was fleeing, the child fell from his arms, and he turned around to see what had happened to him. And then two more shots were fired, one which pierced his head, the other his arm.

A Jew who was passing by and heard the Rav's screams, and shouted at the murderer: "What have you done to our Rav?" In response, the Arab aimed his gun at the man, and shot at him too. Miraculously, he was only slightly injured.

Meanwhile, the child ran to the yeshiva, and cried out: "Our great Rav is wounded. An Arab has shot him." The yeshiva students ran outside and headed for the scene of the shooting. They found their beloved Rav lying in his blood.

The Arabs who had gathered around him, blocked the taxi which had been hailed to take him to the hospital, and rejoiced over the suffering of their enemy. After much effort, the Jews managed to place him in a car, which brought him to the Rabata Hospital. On the way, his student felt that the Rav's soul had departed, and cried Shema Yisroel. When they arrived at the hospital, all that the doctors could do was to pronounce his death.

The bitter news shocked all of the residents of the city. All assembled beside the bais medrash which was near his home, and from there the funeral proceeded. The many Jews who followed his bier cried out in pain, "Woe to the master; woe to his glory"

— in heart-rending tones.

It was not by chance that the murderer had selected the Rav of all the Jews of Tunis — R' Matzliach Mazuz — as his victim. He knew that this would constitute a mortal blow for the Jews of Tunisia, as well as for all world Jewry. R' Mazuz's greatness in Torah, his wisdom, his vast knowledge of the halacha, and his remarkable personality traits were well-known. He had gained worldwide acclaim as a brilliant dayan. All of the questions, in the land, even the most difficult ones, were presented to him. From all over the world, people turned to him, accepting his halachic rulings, and delighting in his sage counsel.

In his series Shut Ish Matzliach, we find that he exchanged views with many great rabbonim, among them, Maharash Halberstam; the Admor of Tzishiov; and the geonim, R' Eliyahu Alankri, a dayan in the city of Chepaks; Chaim Churi; R' Ovadia Hadaya from Yerushalaim; and the Rishon leTzion, HaRav Uziel.

Rabbenu's Background

The beginning of the illustrious Mazuz family dates back ten generations. In the introduction to the book of responses, Ish Matzliach, the author presents a biographical sketch of his family, going back three generations.

The father of the family (described in the introduction to the book Kisei Rachamim), was the famous and outstanding dayan, R' Menachem Mazuz. He was a dayan in the Djerban city of Chara Kabira. He had three sons: R' Shimon, R' Rachamim and R' Chuati, His middle son, R' Rachamim, author of Kisei Rachamim on Tehillim was orphaned at the age of eighteen. He grew up in the city of Djerba, and became the head of its community.

Kisei Rachamim was widely accepted, and studied by many sages. It is replete with wonderful chidushim, words of mussar, and many wise sayings. When preparing the second edition of this book, he fell mortally ill when he reached the words, "Hashem will support him on his bed of death." He died on the 13th of Kislev, 5669, when he was only forty-nine years old.

R' Rachamim had five sons: Menachem, Rephael, Kamus, Meutak and Yosef, all of whom became talmidei chachamim.

His son, Rephael was a great tzaddik who supported Torah scholars, pursued kindness and was meticulous about all the mitzvos. He would often conduct taaniyos dibbur.

In his old age he would abstain from speech nearly every Monday and Thursday. On those days, he would try to avoid people, so that they would not notice his conduct. When he felt that people would sense that he was refraining from speech, he would break his Taanis momentarily, and answer those who approached him. He would rise for tikkun chatzos nearly every night.

While in Djerba, he would rise at the precise moment of chatzos — a time which kabbalists regard as most propitious. For this purpose, he purchased a black rooster (which crows at chatzos) and placed it on the porch to his room. He died on Friday night, the 19th of Av, 5726.

His son, R' Matzliach Mazuz, was born on a Friday night, the 26th of Cheshvan 5672. He was his parents only child, and was called, at birth, Chaim Kadur Matzliach.

After his bris, his father visited his mentor, the RaNaK, who had not been able to participate in the celebration because he was blind. The father brought the infant to the sage after the bris in order to receive a blessing. When the sage heard the name of the child, he said: "I am certain that he will be a wise man in Israel."

To this the father replied. "A blessing — I understand. But why are you certain of this?"

The RaNaK replied: "His name indicates this, because its initials are ches, chaf, mem — the letters of chacham!"

When R' Matzliach was two years old, his family moved to Tunis. In the year 5675, an emissary from Eretz Yisroel, the famous kabbalist Tarab, lodged in their home. In gratitude for the hospitality he had received, he wrote an special amulet to guard the three year old child. He then handed it to the father, and told him to place it in a silver case.

The next morning, when he arose, he called R' Rephael and told him: "In my dream I was told: `Don't you not recognize the great worth of the child for whom you wrote a standard amulet?' And so I must write a new and special one for you."

He then proceeded to write an amulet called "Ha'ilan Hakadosh" and both amulets remained in the silver case until R' Matzliach's death, which was decreed by Heaven due to the many sins of the Nation. Armed with this amulet, he would enter the courts of kings and princes, and nearly all of his requests for the sake of his People were granted.

He grew up in the suburb, Ariana, near Tunis. His father owned a food supplies store. The family lived in a spacious apartment, and led a comfortable life.

When the young Matzliach was ready to study gemora, it was very difficult to find a suitable teacher for him. Each time he would return home, he would find his mother in tears, pleading to return to Djerba, a city of sages and scribes. "I would rather live in a small and musty house," she would say "so that my son can learn Torah."

Toward the end of the year 5682, the family sold its apartment and store for half its worth, and returned to Djerba. Matzliach was ten years old at the time.

When he was fourteen, he had already written halachic responses which amazed all who read them. One of his responses, which appeared in the book Yaskil Avdi, was sent to the gaon R' Ovadia Hadaya. R' Hadaya thought that its writer was a famous rav who occupied an important position as a dayan, and in his reply to him even asked him to supervise a fund raising campaign for the Beit El yeshiva of Yerushalaim.

In 5690, he married his cousin, the daughter of R' Menachem Mazuz, an illustrious sage whose brilliance is evident in the comments he made on his father's books.

R' Matzliach taught Torah in the yeshiva of Chevras HaTalmud in Tunis for three years. His difficult financial situation brought him to learn the watchmakers' trade, and in a very short time, he became an expert watchmaker. He was happy at the opportunity to fulfill the dictum of our sages that "a man should always learn a clean and easy trade."

However, working at his trade did not deter him from immersing himself in Torah learning. The responses and chidushim which he wrote during that period demonstrate how deeply engrossed he was in Torah at that time, and how secondary his trade was for him.

In the year...[date unclear in text] he began to preside as a dayan. In 5715, he was asked to supervise divorce proceedings. During his term of office, he did much to advance shalom bayis, and it is said that he never gave a divorce until all efforts to restore family harmony had proven fruitless.

He was murdered on the 21st of Teves, 5731. All of world Jewry was shocked by his murder. After much effort, his aron was brought to Eretz Yisroel. He is buried in Har HaZeisim in Yerushalaim.

|