| | Feature

The Aliya of Rav Yehuda HaChossid in 1700

by Y. Rossof

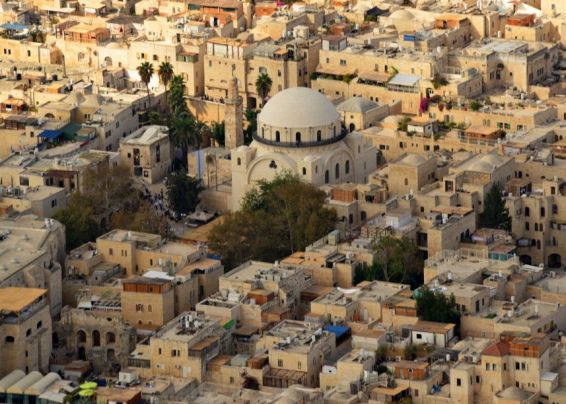

The rebuilt Hurva shul is once again a dominant building in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem

This was originally published in 2006.

The tragic episode of the collapse of the greatest aliya until modern times — that of Rav Yehuda HaChossid and his followers — stemmed from one of the noblest visions of a selfless man. Rav Yehuda of Shidlitz, Poland, labored to become a vessel worthy of Hashem's light, living a life of self-abnegation and devote Torah study. At about the age of sixty he decided that the only place where a Jew could truly perfect himself was in Eretz Yisroel, and began planning to ascend to the Holy City.

For Part II of this series click here.

A Legend in His own Time

Wednesday, the first of Cheshvan, 1700 (5461), was a historic day for the small Jewish community of Yerushalaim. Everyone went out of the city gates to greet the arriving European rav and his thousand plus followers. There had not been such a massive aliya in thousands of years! (The only resemblance to an aliya on this scale was the 13th century arrival of three hundred baalei Tosafos in Israel.)

Rav Yehuda HaChossid was a great talmid chochom and a charismatic figure. Wherever he went and spoke, he captivated his audience by the depth of his genuineness. He spoke from the heart to the heart. His theme was direct: we must all repent and cleanse ourselves, we are G-d's chosen people and should take on the holy tasks which we were created for. The time of the redemption, he taught, is dependent on our rising to the occasion and dedicating our lives to the ultimate cause. We must go to Yerushalaim, he told the people, and there Hashem will fulfill the words of His prophets.

In the Spring of 1699 (5459), Rav Yehuda set out with a following of thirty families from the Polish town of Shidlitz near Grodno. They traveled through Hungary, Germany and Italy on their way to Eretz Yisroel.

The news of their journey spread like wildfire throughout Europe. Gedolim praised him, scholars and laymen listened and a surprising number cast their lot with him. Many who chose to remain still donated handsomely to the cause.

The author of Meoros Nosan, Rav Nosson Nota, joined the group. He described the experience in these words: "A huge kehilla of uplifted Jews, each G-d fearing (including elders and scholars of esteem), stood with a luster shining about them. At their head was one full of wisdom, an angel of Hashem... Rav Yehuda.... [they all were] with one intention: to go and ascend to Yerushalaim, the place of our inheritance."

One thousand five hundred men, women and children joined Rav Yehuda Chassid along the way. Yet the journey by land and sea took its toll: some five hundred died on the way. That fall, after Rosh Hashanah, 5461, they were on the last leg of the journey before setting sail for Eretz Yisroel. Spirits were high, the winds were good, and a seventeen day journey brought them to the Jaffa port.

More disastrous in the long run was the participation of a sinister character by the name of Chaim Malach. He advocated the philosophy of Shabbsai Tzvi, ym'sh, and secretly tried to indoctrinate others into it. He anticipated the second "revelation" of the Tzvi, ym'sh, in 1706, forty years after his conversion to Islam.

The Chacham Tzvi had denounced him as a heretic, yet the noble leader did not take his warning to heart. Now, what would unfold in the coming days, weeks and months was one of the most saddest episodes in Jewish history.

The ruins of the Churva shul soon after it was destroyed by Jordanian soldiers

The Domino Effect

Between that Wednesday, when the Ashkenazi group first arrived, and the following Shabbos, a series of events took place. As everyone arranged for living quarters, Rav Yehuda Chassid mobilized his energies toward purchasing a synagogue and courtyard. He also helped others rent quarters, giving many an outright monetary gift.

By Friday he had already signed an agreement to buy the area which would be later called Churvas Rabbi Yehuda Chassid. It comprised a synagogue with a forty-room courtyard. The Arabs later called it Dir al-Ashkenaz.

Erev Shabbos, as Rav Yehuda immersed in the mikveh and prepared to go to shul, he felt sick. After kabolas Shabbos and ma'ariv, he returned to his quarters and collapsed on his bed, in a semiconscious state. He was delirious, muttering verses from the Torah. His son-in-law, Rav Yeshaya, was by his bedside.

Although the hour was late, he ordered that the famous Sephardic doctor, Rav Mordechai Malki, be brought to examine Rav Yehuda. At the time, the Moslems did not allow Jews to walk outside at night any later than half an hour after dark. The only exceptions made were for doctors and midwives. Dr. Malki, after examining his patient, concluded that there was nothing to be done for twenty- four hours, and with a heavy heart he returned home.

On Shabbos morning, Rav Yehuda woke feeling completely recovered. He joined the services, and publicly apologized for causing his followers anxiety on Shabbos night. When he returned home he collapsed again, and went into a coma. On Monday, 6 Cheshvan, he was niftar.

His levaya was the same day. The entire Jewish community gathered in the new Ashkenazi courtyard to pay their last respects. The Sephardic cantor led the eulogy in the traditional Sephardic manner. Afterwards, the levaya proceeded to the slopes of Mount Olives where he was laid to rest in a large cave. Within a year, his wife and only son also were niftar and were buried there.

The Ashkenazim were left like a flock without a shepherd. The state of shock was not easy to overcome. As a series of other problems complicated life, some of the newcomers started to return to Europe. As the burden of poverty inhibited their spiritual and physical lives in the coming years, more returned to Europe. In the end, the whole community collapsed and the dream of the true chassid and his followers never came to fruition.

A map of Jerusalem's Old City showing the location of the Churva shul

The Wheel of Fortune

It is well-known that the remaining followers of Rav Yehuda eventually became impoverished, and remained with an outstanding debt to the local Arabs. The borrowers were identified as the Ashkenazic community, and the indigenous Sephardic Jews were not held responsible. As a result, Ashkenazic Jews could not live in Yerushalaim for more than 100 years, since any arriving European Jew was immediately held responsible for his compatriots' large debt.

This classical story of the impoverished Ashkenazim being oppressed by cruel Arab debtors, though true, needs to be put into perspective. How could they fall into such debts from the very outset when they came with ample financial resources?

One of the foremost travelers, known as Rav Gedaliah, wrote a detailed booklet of what transpired during this period called, "Sha'alu Shelom Yerushalaim." Rav Gedaliah writes:

The cost of the synagogue and the adjacent rooms was much more than expected. First of all, the kadi had to be bribed before he would permit us to build. According to Turkish law, it is illegal to make any changes in the size of the building, even after a building permit is issued.

Since we wanted to enlarge the shul, the kadi demande? a much larger bribe. He reasoned like this: since a new Jewish synagogue must pay a tax of 500 talars per year for three years, it is only fitting that an extra 500 talars per year be paid to him for allowing the expansion of the shul. These taxes were unforeseen and caused us to go into debt. Our debts mounted as we had to pay bribery money for every little thing the Arabs did for us.

The yearly taxes of two adumim per adult male, though it applied all citizens of the city alike, became increasing difficult for us to pay. Although everyone in the Ottoman Empire was obligated to pay this tax, the citizens of Hebron were exempt as a tribute to the Patriarchs who are buried in Machpelah.

Everything snowballed after all the unforeseen expenditures for the synagogue. Within no time the debts zoomed over our heads. As soon as we got out of the clutches of one Arab lender, we fell into the hands of another.

Before long, we were afraid to walk in the streets during the day for fear one of them would apprehend us. At home the situation was appalling. We lacked even the basic necessities. In truth, before immigrating, Rabbenu (Yehuda HaChossid) had traveled throughout the Rhineland and had received assurances of financial backing. What was unforeseen were the astronomical sums necessary to keep us out of jail. Imprisonment is the worst thing. Therefore, we were left stripped of everything...

Also, it was impossible for us to work. First, the language barrier: none of us spoke Arabic or Ladino, nor did they speak our language. Second, it is forbidden to sell them (Moslems) intoxicating beverages, like beer and wine. If someone is caught — because the Arab got drunk — the Jew is flogged and penalized heavily. And last, no Jew — including the Sephardim who speak the language — can set up a business which involves long distance traveling since the roads are dangerous due to highwaymen. Even the Arabs travel in caravans, which for a Jew may have many halachic problems.

There are a few Jewish storekeepers in Yerushalaim. In order to protect themselves from Arab thievery, they take an Arab friend as a partner. There is one group of local Jews, called Morishkas, who are fluent in Arabic and whose dress is similar to the local Arab dress. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between them since they both do not shave their beards. The Morishkas own donkeys and travel from village to village selling spices and other wares. They also buy wheat and other food stuffs to sell in Yerushalaim. Still, most of them are paupers. If this is the lot of those Jews who speak the language and are engaged in business, how much more desperate is our situation.

The interior of the rebuilt Churva shul

A Tzaddik from Italy

In Adar, 1702, a wealthy Italian kabbalist moved to the Holy City, at the head of a group of twenty-five followers. Rav Avrohom Rovigo was a kindhearted man who loved those who studied Torah.

In his hometown of Modena he supported a yeshiva, and propagated a love of Jewish mysticism. Although he never published anything, one of his disciples did. Rav Mordechai Ashkenazi wrote a commentary on the Zohar, which he entitled Eishel Avrohom, after his mentor who supported him for years.

Rav Rovigo planned to open a yeshiva in Yerushalaim. In the first weeks, tragedy struck the group. Rav Mordechai's wife died in childbirth, then his daughter, and finally he and his two sons passed away. Rav Rovigo, saddened by his chain of events, continued to build his yeshiva. Members of Rav Yehuda's group joined them. Among them were Rav Yeshaya and Rav Nosson Nata.

The latter found a soul-mate to study with in the person of Rav Yaakov of Vilna. They studied Kabalah together and co-authored Meoros Nosson. When, some years later, Rav Nosson was forced to go on shlichut to Europe, he wrote: "Yet leaving Eretz Yisroel is so difficult, even for an hour."

Very quickly Rav Rovigo also befriended a man of unique stature. Rav Raphael Mordechai Malki was the epitome of a Torah sage who gave himself over to the community. He had moved to Yerushalaim over a quarter of a century before, and had built up a reputation as a scholar (he was a dayan), a doctor and a communal leader. He had lived through the good years of the 1670's and 1680's, and never considered leaving during the lean years of the 1690's and the first years of the 1700's. His two sons-in-law were gedolim: Rav Hizkiah Silo (the author of the Pri Chadash), and Rav Moshe Hagiz.

His unpublished commentary to the Torah included comments on medicine, a picture of the times, and ideas of how to better the spiritual and physical life of his fellow Jew. Part of his writings were later published as Likutim. He died around 1704.

Besides bringing the light of Torah into Yerushalaim during a period of austere darkness, Rav Avrohom Rovigo did everything he could to help his Jewish brethren. In the end, he decided to go as a shaliach and collect for the community. He took one of his disciples, Rav Chaim Chazan, along with him. Rav Rovigo died in Italy in 1713. Whether he went once or twice as a shaliach is unknown. But his sole aim was to better the lot of his downtrodden brothers in the Holy City.

Rebellion

In 1703 a rebellion broke out. An influential Arab by the name of Nakib, together with a couple of hundred comrades, took control of the city. When the Pasha came in the Spring to collect the yearly tax for the Sultan, he found the gates locked and squads of Arabs on the wall with their bows drawn. The Pasha retreated and sent a message to let him enter. According to Turkish rules, the Pasha was forbidden to shoot arrows into the city in deference to the city's holiness. The rebels, on the other hand, were free to shoot at anyone outside the walls. After a few weeks the Pasha returned to Constantinople.

The other residents of the city, though innocent, were trapped as pawns in the rebellion. Many of the rich Moslems went hungry during those weeks, and the impoverished ones lived on thin air. In an attempt to save themselves, the citizens of the city smuggled a letter to the Sultan begging mercy. They were simply innocent bystanders. Nakib and his companions alone were responsible for the insurrection.

This went on until the winter of 1705-1706. The Sultan could not be bluffed. He sent a commander with an army of Turkish soldiers. The news of the approaching army gripped everyone with fear. The prominent Arabs entered Migdal Dovid for safety. Nakib entrenched himself in his fortified house nearby. A feud broke out between them, each side shooting arrows at the other. Finally, Nakib called out that he would meet with the Turkish general and acquiesce to his demands.

The general sent a message to the influential Arabs asking their assistance at bringing Nakib to him alive. The Sultan wanted him brought before him before sentencing him to death. The message somehow got into Nakib's hands. When he realized what awaited him, he escaped in the middle of the night with several hundred men. The army entered though the gates the next morning.

Although the residents were free of charges of insurrection, they were forced to pay dearly for their freedom. Some of the wealthy Sephardim left the Holy City. Soon a new commander arrived from Constantinople who took up residency to ensure the peace of the Yerushalaim.

The Churva shul as it appeared in the 19th century

.jpg)

End of Part 1

|