| | NEWS

Shomer Tziyon Hane'emon:

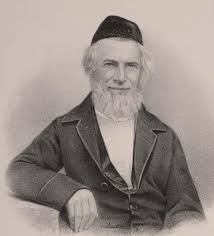

The Hundred and Fifty-Third Yahrtzeit of the Oruch Le'ner

By M. Musman

This appreciation of HaRav Yaakov Ettlinger was first published in 1996, twenty-eight years ago, on the occasion of his 125th yahrtzeit.

For Part II of this series click here.

Part One: His Life

The first Chanukah light is kindled as darkness descends after the twenty-fourth of Kislev. This ushers in Chanukah as well as the yahrtzeit of HaRav Yaakov Ettlinger, zt'l, the author of the Oruch Le'ner commentary on the gemora, one of the best known German gedolei Torah of recent generations.

The two anniversaries have much in common. During Chanukah, we commemorate the victory of faithful Jewry over the Greek oppressors and the miracle with which Hashem indicated His acceptance of their efforts. HaRav Ettlinger's lifetime, over two thousand years later, saw the ripening of the first bitter fruits of the rapprochement with German culture that had been facilitated by Moses Mendelsohn.

The twin ills of assimilation and Reform began to rear their heads in many Jewish communities across Germany. This called for a positive response from the Torah-faithful segment of Germany, the oldest Jewish center in Europe. That response was pioneered by HaRav Ettlinger.

His greatness in Torah and perfection of character illuminated the lives of many who were perplexed by the tempest into which German Jewry found itself plunged as the doors into the surrounding Gentile society, that had been firmly bolted for centuries, slowly swung open. He coordinated public protest against the reformers and, over the years, undertook a range of other measures aimed at remedying their destructive influence. In addition, many of the disciples he raised went on to further the campaign to proclaim the Torah's truth.

While the twenty-fifth of Kislev therefore provides a fitting opportunity for surveying the extent of HaRav Ettlinger's impact as one of the Torah leaders of his time, his Torah is a source of brilliant illumination that outshines any particular date. His Torah is studied year round in botei medrash all over the world, where his seforim are numbered among the relatively few in recent generations that have become universally accepted as standard works which accompany the learning of the masechtos they elucidate.

The palace in Karlsruhe

Cradled in Antiquity

Soon after the town of Karlsruhe, in Baden, Southwest Germany, was founded at the start of the eighteenth century, a Jewish community was established there by Jews from the neighboring town of Ettlingen. Among the distinguished rabbonim who led the community of Karlsruhe over the years were HaRav Nesanel Weil zt'l, author of the commentary Korbon Nesanel on the Rosh, and his son and successor, HaRav Yedidia Tieh Weil zt'l.

One of the community's notables during the latter's tenure was the parnas, Rav Meir Ettlinger, the grandfather of the Oruch Le'ner, himself the son of distinguished forbears. His son, Rav Aharon, an exceptional and unassuming talmid chochom, was appointed as the head of the regional kloiz, where his own gifted young son, Yaakov `Yokev,' who was born on the twenty-ninth of Adar I, 5558 (1798), the year of the petiroh of the Vilna Gaon, soon joined the many talmidim who flocked to hear his shiurim.

His father was his first teacher and guide, to whose training HaRav Ettlinger attributed all of his later attainments. In his introduction to the Oruch Le'ner on Yevomos, he writes of his parents: `The fruits of my understanding are [from] what they planted; [it is] their own which I am setting before them in Hashem's garden, to give luster to their neshomos. I was the child in whom they delighted. They tended me upon their lap, taught me the path of holiness, the path of life. They planted me like a tree next to rivulets of water...'

Writing elsewhere of his father he says: `...and raised me among wise men; I drew from the well of living waters of my father's wisdom.'

It was Rav Aharon Ettlinger who encouraged his gifted and retiring young son to put his chidushim into writing. HaRav Ettlinger made a point of including some of his father's chidushei Torah at the conclusion of each of his own seforim. They continued to exchange Torah correspondence after HaRav Ettlinger left Karlsruhe.

Yaakov Ettlinger was still a young boy when HaRav Yedidia Weil zt'l passed away and was succeeded as rav of Karlsruhe by HaRav Asher Loeb Wallerstein zt'l, the only son of HaRav Arye Leib of Metz zt'l, the author of Sha'agas Arye. HaRav Asher inherited his father's legendary sharpness and the young Yaakov Ettlinger became his talmid.

The principle of seeking only the truthful meaning of Chazal's teachings, eschewing the pilpul that was then still popular in many Torah centers, guided HaRav Asher throughout his life. Instructing his son-in-law before he was niftar, Rav Asher summed up his method thus, `All your efforts should be [directed] towards following the path of the truth, understanding Chazal's words through making genuine comparisons, speaking words which are relevant and not swerving from the straightforward, truthful meaning and may Hashem... lead us along the path of truth.'

This was also the path which his talmid, HaRav Ettlinger, followed. Replying to a letter from one his sons-in-law, he wrote, `It gave me immense pleasure to see that you are learning with great application, basing yourself upon foundations of truth and straight thinking.'

Even when the intricate, involved pilpul led to a conclusion with which he agreed, he still shunned it as a method of learning; how much more so when it did not! An inspired flash of logic would not win any compliments from him unless it was in line with the straightforward meaning. `Although this is something intellectual, in my humble opinion, it does not approach the truth,' he commented in one of his teshuvos.

When he approved of an assertion, he would praise it for its truth as, `something correct, according to the true meaning of the Torah.' However, he did not feel it was necessary to go to great lengths to use logic in order to provide support for self-evident truths. `It is my practice to write briefly where there is no danger of mistakes being made,' he wrote. The truth spoke for itself.

Karlsruhe in Germany

Winds of Change

As rav of Karlsruhe, Rav Asher Loeb was also the head of the supreme council for the Jews of the state of Baden (this was the Oberrat, established by Government edict in 1809). It was his job to oversee Jewish communal life in the region.

Writing to one of his talmidim in 5572 (1812), he bemoans the dwindling dedication to Torah learning amongst German Jews. `I found, in our many sins, a wide breach in this land, most of whose inhabitants have withdrawn their sons from the beis hamedrash, which will lead, chas vesholom, to Torah's becoming forgotten amongst Jews.'

This trend was also noted by HaRav Meir Lehmann, who, in his commentary to the Haggadah, notes that, `Just two generations have passed since the days of the flowering of the German yeshivos. In their genuine, deep piety, the communities enabled the study of Talmud to reach a peak, by maintaining yeshivos in every center of Jewish population. Prague, Fuerth, Frankfurt-am-Main, Mainz, Worms, Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Berlin, Breslau, Frankfurt-am-Oder and Halberstadt were just some of the many communities to which [students] flocked from all over Germany in order to imbibe Torah from the [local] yeshivos.

`What laid waste to the glory of German Jewry was the dreadful controversy surrounding HaRav Yonoson Eibuschitz. The youth were no longer attracted to the yeshivos which were the crown [of the communities], and they closed under the heavy lock of strife and discord. This pandemonium wreaked havoc with the lofty ethics and the fear of Heaven that had been imprinted on German Jewry ever since the days of the Chassidei Ashkenaz. The abyss of assimilation that has opened up in our times has swallowed all whose faith was weak. I am unable to record even the beginning of all that has come my way to hear.'

The forsaking of Torah was the beginning of the spiritual ruin of German Jewry. Once that had happened, the pressures of the march into modern times caused many to fall by the wayside.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the winds of liberalism were blowing from Paris and urban economic life was becoming modernized. In the hope of easing the unfair burdens imposed upon the Jews by the hostile surrounding society, a battle was being waged by certain elements of the Jewish population for political and civil emancipation and it was slowly being won. As a result, Jews were increasingly able to attain positions in German society which left them far more exposed to the new ideas and trends than they had ever been before.

Karlsruhe Synagogue in 1810

All these changes would have exerted pressures upon German Jewry anyway. However, had there not already been a large-scale defection from Torah study, the community as a whole might have emerged from these confrontations with its allegiance to Orthodoxy more or less intact. As it was, the weakening of the bonds to Torah led many to adopt a distorted view of the position of the Jews, which led them to conclude that in order to facilitate the process of their emancipation, traditional Judaism had to be modified in order to bring it more in line with the surrounding society.

Moses Mendelsohn has always been regarded as the initiator of this process, by virtue of his advocacy of secular enlightenment, and the publication of his German translation and commentary to the Chumash. Although he did not (openly, at least) propose the wholesale dismemberment of Judaism, but the opening of a conduit which would bring the influences of modern European culture to bear upon the Jews, the gedolei Torah of the time were aware of the danger inherent in such a step and they roundly denounced his efforts and aims.

Indeed, once the process began, it quickly snowballed and got out of hand. What began with an acquaintance with German culture, progressed extremely rapidly to the opening of a number of "reformed" Jewish schools (not Reform, for a Reform Movement as such did not yet exist), where German was the language of instruction and general studies replaced Talmud. These soon led to an epidemic of apostasy and intermarriage.

It did not take many years before Mendelsohn's heirs turned their attention to the drastic reorganization of their own religion. With the deepening ignorance of the fundamentals of Judaism and increasing exposure to gentile society, the calls for making radical changes in the Jewish religion that were being voiced by influential Jews, whose sentiments were more German than Jewish, grew louder and more insistent, and popular sympathy with them increased likewise.

Steeled for Battle

As a young man, the Oruch Le'ner spent several years in Wurtzburg, Bavaria, learning in the yeshiva of HaRav Avrohom Halevi Bing zt'l, who was Rav of the region and one of the foremost talmidim of HaRav Nosson Adler zt'l, of Frankfurt who was also a rebbe of the Chasam Sofer.

According to one contemporary, HaRav Bing's yeshiva produced most of the rabbonim who occupied communal positions in Germany in the mid-eighteenth century. Amongst the better known talmidim of HaRav Bing were Rav Dr. Nathan Marcus Adler zt'l, Rabbi of Hanover and then Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Rav Eliezer Bergman zt'l, author of Behar Yeiro'e, Rav Yehoseif Schwartz zt'l, author of Tevuos Ha'aretz and Devar Yosef (these latter two settled in Eretz Yisroel, where they founded Kollel Ho"D [Holland VeDeutschland] in Yerushalaim), Rav Avrohom Rice zt'l, who emigrated to the United States, where he settled in Baltimore and is remembered today as the first fully-qualified rav to arrive in that country, and Rav Yitzchok Dov Halevi Bamberger zt'l, who succeeded his rebbe as rav of Wurtzburg and marbitz Torah in Bavaria.

While learning in Wurtzburg, the Oruch Le'ner also engaged in general studies in connection with the town's university. His undertaking such studies must be understood in the light of times that German Jewry was experiencing, as outlined above. In order to successfully defend Judaism from the onslaught of the early reformers, and also to anticipate the dangers that awaited faithful Jews in their encounters with the new times, it was necessary to be acquainted with the currents of modern knowledge, thought and ideas, not for their own intrinsic worth, but because they exerted a powerful influence upon the society in which the Jews lived.

In 5632 (1872), the journal Halevanon published a hesped for HaRav Ettlinger, written by Rav Dovid Weiskopf zt'l, rav of Wallerstein, who had become one of his close friends during their years together in the yeshiva in Wurtzburg. The following extracts portray the Oruch Le'ner as bochur and convey an accurate picture of how he approached the secular studies in which he had to engage at that time.

"...[He] was then an extremely pleasant bochur, one of Hashem's choicest. He arrived from his father's home suffused with a wealth of Torah which he had learned and understood from his teachers, Rav Asher zt'l, and his father Rav Aharon zt'l. He was already great in Torah, in wisdom and in knowledge and his fear of Heaven was the basis of his firm Torah [knowledge.] He drew himself close to HaRav Avrohom Bing zt'l, in order to deepen his comprehension of the Torah's truths...

"With what application Yaakov, the perfect one, kept himself inside the tent of Torah!... He only went to listen to [lectures on] other disciplines for a few hours, a few days each week, on account of the requirements of the times and for knowledge of worldly matters, just enough to be able to `say to wisdom you are my sister,' and to know how to reply to the unfaithful, the heretics and the apostates. Even at those times, he never removed his thoughts from contemplation of the holy Torah; his mouth never interrupted its involvement in Torah and in mitzvos, to which he greatly applied himself. On most days, he was up half the night, for Hashem's Torah was his delight.

"He was extremely frugal, eating plain bread and never partaking to his fill of any food... even though his needs were amply met by his family. [He did this] in order to benefit to a greater extent with a clear mind, from Hashem's Torah, which is a restorative to the soul. He also undertook many voluntary fasts, however, his eyes did not miss a moment's Torah study as a result of this and Hashem blessed his strength."

According to a family tradition, prior to attending any university lecture, the Oruch Le'ner lifted his heart in supplication to Hashem that he not be harmed by in any way by what he was about to hear. His tefillos were accepted for later, as rav of Altona, a popular saying in the town was that, `the Satan was unable to defeat our teacher when he learned in Wurtzburg.'

His concern about engaging in secular studies is clearly articulated in the collection of his droshos, Minchas Oni, where he describes them as soul-destroying, if insufficient care is exercised in retaining a proper perspective regarding their true importance in life. He writes, `One's thoughts can easily lead one to stumble from the permitted to the forbidden, bringing destruction to one's soul.' (Parshas Tazriya p.52)

The Chasam Sofer's view on secular studies which are undertaken in order to provide an effective response to heresy, were similar to those of HaRav Ettlinger (to whom his remarks may have been referring). Quoted in a letter written by the Maharam Shick, the Chasam Sofer compared such students to Rabbi Akiva, who `entered the pardes [of hidden Torah teachings] at peace and came out at peace.' `In the same way, those for whom Torah is the main thing, yet the breaches of this generation compel them to take a smattering [of secular disciplines] from the evildoers in order to sweep the latter aside and utilize the former to strengthen our holy Torah — they [the studies] will not harm them and they are not forbidden to such people.'

The Oruch Le'ner's three years in Wurtzburg came to an abrupt end when an antisemitic pogrom erupted in the town. Apparently this was in the summer of 1819, when pogroms broke out in several South German towns in response to the authorities' easing certain discriminatory economic regulations for the Jews of the region.

Cries of "Hep! Hep!" rent the air as bands of ruffians roamed the streets. Some of the thugs broke into the Oruch Le'ner's lodgings and he was advised by the house owners to leap quickly out of a back window into the garden in order to escape them. He left Wurtzburg.

On his way home, HaRav Ettlinger spent some time in the town of Fiorde, learning in the yeshiva of HaRav Avrohom Wolff Hamburg zt'l, a great tzaddik and talmid chochom, author of the works Sha'ar Hazekainim, Simlas Binyomin and others, whose life was mercilessly embittered by reformers, who ultimately succeeded in having his yeshiva closed down, his talmidim dispersed and in driving him out of every public office in his community.

Teacher, Guide and Leader

`From the day I reached maturity, crowds [of students] flocked to me, many of whom today occupy rabbinical positions,' (the Oruch Le'ner, in his introduction to Bikurei Yaakov).

Upon his return to Karlsruhe, HaRav Ettlinger began to deliver regular shiurim. The town's most distinguished talmidei chachomim participated in the shiurim he delivered on Sanhedrin when he was just twenty-two years of age. At his father's urging, he recorded these chidushim, which later served as the basis for the Oruch Le'ner on that masechta.

In addition to his excellence in lomdus, he earned a reputation as a gifted public speaker. For example, a published collection of the sermons he gave as a young man contains an address he delivered in the Great Synagogue of Karlsruhe on the occasion of the coronation of Grand Duke Ludwig Von Baden in 1824.

In Elul 5585 (1825), he married the daughter of a distinguished parnas, Reb Kaufmann Wormser of Turlach and two and a half months later, in Cheshvan 5586, he took up a position in Mannheim, as head of the town's kloiz. The kloiz was a beis hamedrash where a group of seasoned talmidei chachomim sat learning full time, supported by the founder or the trustees of the kloiz.

The Mannheim kloiz had been founded many years before by a wealthy member of the community who set aside a large sum of money for the upkeep of the institution and also left precise instructions as to how it was to be run. Over the years, many famous rabbonim had led the community and disseminated Torah as heads of the kloiz, which served as a Torah center for the whole region of Baden.

HaRav Michel Sheier zt'l, the last rav to serve in this joint capacity, was niftar in 5569. Rav Hirsch Traub, who succeeded him as rav, was joined several years later by the Oruch Le'ner, who, in his first drosho in the kloiz, expressed his approval of the division between two rabbonim, of the two tasks that had always traditionally been borne by one.

HaRav Ettlinger opened a yeshiva in the Mannheim kloiz, whose seventy students hailed from all over Germany. Although little is known about the yeshiva itself, a survey of the list of talmidim shows that many future German rabbonim were trained there, the most famous of whom was HaRav Shimshon Refoel Hirsch zt'l, who arrived from Hamburg. The statement quoted at the beginning of this section is clearly borne out.

The Oruch Le'ner also served as rav of the town Ladenburg and its district. In 5587, he was chosen to serve as a member of the Baden district Oberrat but his involvement with this committee did not last long.

At one of the meetings in 5589, a group of participants wished to gain control of the appointment of rabbonim. This group, with their reformist tendencies, were liable to destroy the remnants of Torah faithful Jewry in the Baden area. With a heavy heart, HaRav Ettlinger severed all connection with the Oberrat. This move won him the admiration of both his supporters and his opponents as a man of steadfast principle and integrity.

Personal tragedy marred the end of the Oruch Le'ner's decade-long tenure in Mannheim when his five year old son Itzik passed away in 5595 (1835). Rav Leib Ettlinger zt'l, a younger brother of the Oruch Le'ner, who had arrived in Mannheim from HaRav Bing's yeshiva in Wurtzburg in order to sit as a talmid at his brother's feet, assumed the mantle of leadership of the kloiz, remaining in Mannheim for the rest of his life.

End of Part 1

|