| | NEWS

The Aliya of Rav Yehuda HaChossid in 1700

by Y. Rossof

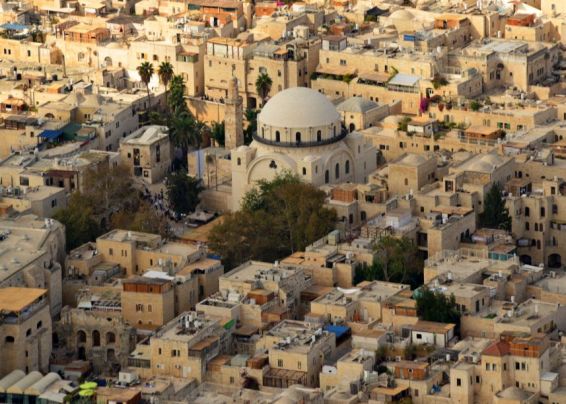

The Rebuilt Churva Shul in the Old City

I>This was originally published in 2006.

The tragic episode of the collapse of the greatest aliya until modern times — that of Rav Yehuda HaChossid and his followers around 300 years ago— stemmed from one of the noblest visions of a selfless man. Rav Yehuda of Shidlitz, Poland, labored to become a vessel worthy of Hashem's light, living a life of self-abnegation and devote Torah study. At about the age of sixty he decided that the only place where a Jew could truly perfect himself was in Eretz Yisroel, and began planning to ascend to the Holy City.

Part 2

For Part I of this series click here.

Shots in the Dark

The money that trickled in from the Diaspora could not alleviate the dire situation in the Holy City. New sources of support for the Ashkenazi community had to be found. Two of them dealt with relations with the Cairo kehilla.

Rav Yaakov, acting as head of the community during the first decade of the 18th century, discovered a problem in the handling of consecrated property from wealthy Egyptian Jews. Over the past twenty years this property had been legally designated for the Jewish community of Yerushalayim.

Unfortunately, unscrupulous Jews of Cairo confiscated the property. When petitioned to release it, they offered to send the profits but not to sell outright the property. Rav Yaakov, after consulting with gedolim, went to Egypt and managed to sell the property. In this way, he was able to return with a substantial amount of money. It a was momentary breathing spell.

The Original Churva Shul in the Old City

In 1711 (5471), Rav Moshe HaKohen of Prague, head of the Ashkenazi beis din, went as a shaliach to Europe. He stopped in Cairo, and was influential in having the Turkish authorities annul the liability for future interest on their loans that had been leveled against the Ashkenazi community in Yerushalayim. He even succeeded in having one third of the debt erased on condition that the remaining two thirds be paid within three years.

However, there was a price for this. The Arabs lenders would take the law into their own hands if the settlement was not fully kept. This was a threat that could even affect human life. As collateral, they demanded that the Ashkenazim put up their synagogue and homes. This was a threat to Jewish property.

Rav Moshe, after conferring with the head of the Cairo beis din, Rav Avrohom Halevi, decided that a special takana be introduced. For the next three years, every European kehilla would give their donations only to Ashkenazi shlichim of Yerushalayim. Thus, they might be able to pay off their large debts. The Sephardic shlichim from Yerushalayim, Hebron and Tsefat were told not to go to any European city during that time.

With this enactment, Rav Moshe headed for Europe. In his hometown of Prague, he collected a substantial ten thousand florins. Nonetheless in 1714, when all the collected efforts were added up, the sum did not meet the total necessary to free the community.

A gentile by the name of Kasan Geyoni offered to lend them over 1,000 talars to save the situation temporarily. It was a one year loan. When the time limit passed, the group desperately begged him to extend it. He agreed to extend it by three years, but only after doubling the interest payment. After that period passed, he burst in on them, enraged, and demanded the principal and all the interest. After desperate negotiations, he agreed to another extension and a handsome interest fee.

These efforts by the sages of Yerushalayim were gallant efforts to save the Ashkenazi kehilla. Every coin collected for the community was a mitzvah of the highest level. Yet, the catastrophe which loomed over the community could not be averted, and in the end, the Arabs took the law into their own hands.

The Rebuilt Churva Shul in the Old City

Churvas Rav Yehuda Chassid

On Shabbos, parshas Lech Lecha, 8 Cheshvan, 1720 (5481), the Arabs suddenly descended on the Ashkenazi synagogue. Without any sensitivity to the sacredness of the place, they set the House of G-d on fire. Benches were used as firewood, pages of holy books as kindling. One after the other, the Sefer Torah scrolls were thrown into the bonfire like martyrs at the stake, until all forty were set ablaze.

Had the synagogue been made of wood, there would not have been anything left but a mound of ashes. Like all buildings in Yerushalayim, the synagogue was built of nonburnable stone. The Arabs rioters stopped short of demolishing the shul. Instead, it became the Moslem garbage dump, and the courtyard homes were converted into eleven Arab shops.

Outside, leading members of the congregation were imprisoned, and everyone else was ousted from the courtyard rooms. Later, all Ashkenazim were banished from the city. Some of them then went to Tsefat, others to Hebron, and others returned to Europe.

No Ashkenazi Jew was permitted to dwell inside the wall of the Holy City. If discovered, imprisonment would be his lot. In the coming generations, a few brave Ashkenazi Jews did manage to get into the city. Dressed in the traditional Sephardic garb, men like Rav Gershon Kitover and Rav Menachem Mendel of Shklov succeeded in dwelling there, but they were the exception.

It would take a hundred years until the ruling government would allow Jews of Ashkenazi descent officially to take permanent residence in Yerushalayim.

Map showing the location of the Churva Shul in the Old City

Rebirth

For a hundred years, the Churvas Rav Yehuda synagogue suffered the humiliation of heathen desecration. The disciples of the Vilna Gaon, called Perushim, came to Eretz Yisroel during the first decade of the 19th century. Led by Rav Yisroel of Shklov, their dream was to settle in Yerushalayim. Alas, they were stigmatized as Ashkenazim, and therefore were forbidden to dwell there. Instead, they planted roots in Tsefat.

When a devastating epidemic lashed across the Galil in 1812, many fled. A number of them came to Yerushalayim and built a nucleus of an Ashkenazi community, albeit secretly. They dressed as Sephardim, and during the week they prayed together in the Or Hachaim synagogue. On Shabbos, they joined the Sephardic minyanim.

Over the years, the Perushim, later lead by Rav Menachem Mendel of Shklov, sought to get a firman (official authorization) from the Turkish government to live in Yerushalayim. There goal was to resolve the hundred year old dispute, annul the debts, and allow Ashkenazi Jews to settle in the Holy City.

It was only in the 1830's when the Egyptians took control for a decade, that authorization was received. After that the Perushim opened their own shul which they called Succas Shalom. It was bought for them by the Lehren family of Amsterdam.

In the Churvah compound they founded and built the Menachem Tsion shul, headed by Rav Shmuel Salant. Commonly called Beit Midrash Hayoshon, it was officially inaugurated in the beginning of 1837.

Later, when the Ottoman Empire regained power in 1840, new leniencies were added. For instance, there was an ancient law that forbade Jews and Christians from building tall religious edifices. High, domed synagogues that would tower over the city roof tops were outlawed. That is why the main Sephardic shuls are built from below ground level, rising only one flight above street level.

The reconstruction of the Churvah — and soon the Tiferes Yisroel synagogue of the Chassidic community in 1860 — were the first exceptions. The Churvah became the center for the Ashkenazim, and the Tiferes Yisroel the center for the Chassidim. They both stood and sheltered words of prayer and Torah for almost a hundred years, until 1948.

In a real sense, they became the crown of the Holy City. Even today, half a century later, when the Tiferes Yisroel synagogue still stand in ruins, they still testify to the grandeur of the indomitable faith of the Jewish people to withstand and survive. In this way, the dream of Rav Yehuda HaChossid came true.

A Dog and the Other Dogs

One year during the first decade of the 18th century, a new kadi (Turkish judge) came from Constantinople. He was a wicked man who devised schemes against the Jews, and even against some of the Moslems.

For instance, he decreed that no Jew could wear white garments on Shabbos (as the baalei kabbala do), nor could they put metal heels on their shoes. The turbans worn by Jews had to be black, and the hat placed in the middle had to be high. All of these measures were designed to make to Jew stand out and be easily identified. During the week, many Jews dressed with low turbans like the Arabs, and were not readily distinguished. (In those days all male Arabs had long beards like the Jews.) This reduced the menace harbored by lowly Arab neighbors.

Next, the kadi sought to humiliate the Jews of the city. Jews had to pass an oncoming Moslem by stepping over to his left side. If not, the Jew could be arrested and imprisoned. Often, an Arab would intentionally walk out of his shop in order to force the Jew to sidestep to the left. It was a new pastime for the lazy Arabs.

Before Purim the kadi discovered that a dog had entered the Moslem areas of the Temple Mount. Enraged that such a despicable creature should profane the holiness of the spot, he ordered that all dogs of the city be killed. To encourage Arab youth to fulfill his decree, he offered them a monetary prize for each dead dog. They eagerly carried out his words, and ran about the narrow alleys of Yerushalayim in search of dogs.

With the dead carcass in hand, they waited for a Jew or Christian to pass by and forced their victim to take it outside the city. An area beyond the city wall at Har Tsion was designated for the burial of the dogs. Christians, who were mostly wealthy, were able to bribe the Arabs and avoid the obnoxious task. But the Jews were poor and had no alternative.

Sometimes, after taking one dog outside the city, a Jew would meet another Arab on his way back and have to go with another carcass. Arab children often taunted them along the way to the burial ground.

This led to a self imposed curfew: everyone stayed home to avoid trouble. But this, too, could not endure for long since the basic necessities of life were lacking at home. It was then agreed in the Jewish community that only men would risk venturing outside to buy household needs.

Before Pesach, Rav Gedaliah, one of the followers of Rav Yehuda Chassid, was grinding wheat for matzos. Together with some other companions, they worked hard to finish the job. Suddenly they heard a group of noisy Arab youths dragging several dead dogs. "We immediately shut the door to the grinding house, and waited fearfully until the wicked Arabs passed us."

The situation persisted even after Pesach. Late in Iyar, on the yahrtzeit of Shmuel Hanovi, many members of the kehilla went as always to his burial cave to pray. During the day, some late comers informed the group that the kadi had just enacted a new twist to his decree. Since there were still some dogs hiding in courtyards and abandoned ruins, every household was responsible to bring one live dog to the wall outside of Har Tsion.

There an officer would kill the dog and present the man with a certificate. Those who did not have such a document within a certain amount of time would be arrested. This decree applied to Arabs as well.

When they got home they realized the full impact of this decree. Dogs were scarce, and even the Arabs had a hard time fulfilling the obligation. Jews had to pay Arabs to find them a dog, and even then there were not enough dogs for everyone.

After Shavuos, the kadi instituted his decree against wearing white garments on Shabbos. Suddenly, he realized that the Jews had gone to the cave of Shmuel Hanovi without a permit. Actually, every year permission was automatically granted by the kadi's secretary, for a set fee. But he was an antisemite who thirsted for an opportunity to bring havoc to the Jews.

He arrested the nosi of the Sephardic community and placed him in detention. The Jewish community shuddered at the news. A fast was decreed, and a community prayer service.

In the meantime, a number of prominent Moslems reacted to the arrest in a different way. They, too, had a list of their own complaints against the kadi, and wanted to get rid of him. The arrest of the leader of the Jewish community only heightened their feelings. The nosi was a highly respected man, and his imprisonment was a breach of honor usually accorded the communal leaders.

They decided to take matters into their own hands and on the second day of the arrest, they forcefully freed the Sephardic nosi from the dungeon. At nightfall, they then marched on the kadi's house.

They were out for blood. The kadi's residence was inside a large fortified courtyard. He knew what they wanted, and quickly wrote a note and threw it out to them. He apologized for his actions, and pointed the blame at someone else. He claimed that his appointment was for a single year and, since he did not know the customs of Yerushalayim nor the language (he spoke Turkish and they spoke Arabic), he had relied on a Moslem advisor of rank, and he was responsible for all the actions he took.

The angry mob quickly found the advisor and slew him. Their anger still at a pitch, they threw rocks into the courtyard. Had the kadi been standing there, he would have been stoned to death. He remained locked inside his house for a couple of days. One night he secretly escaped and returned to Constantinople.

(The material for the episode of Rav Yehuda HaChossid during the first decades of the 18th century is culled from the eyewitness report of Rav Gedaliah (Sha'alu Shalom Yerushalayim), and Toldot Chachmei Yerushalayim (vol. II, ch. 9).

The Rebuilt Churva Shul in the Old City

Modern Times

When the Jordanian Arab Legion got control of the Old City of Jerusalem after the cease fire in 1948, one of their first acts was to blow up the Churvah. Even after Jews regained control of the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967, the Churvah was not rebuilt for a long time.

In 2000 plans were approved for the reconstruction of the synagogue. It was built to resemble the 19th century Ottoman synagogue with four huge pilasters on each corner and four dramatic stone arches on each face of the building supporting a large dome. Jerusalem architect Nachum Meltzer designed the new synagogue which was inaugurated on March 15th, 2010.

It stands on the west side of Churvah Square, one of the tallest buildings in the Old City, crowned by the magnificent white dome. Beneath the dome is a railing encircling the balcony where you can get 360 degree views. The synagogue has elongated arched windows, many with stained glass.

Inside the synagogue's high ceiling reaches up to an inner balcony and the underside of the dome. The many windows flood the space with light that reflects off the white walls. On the east wall is the synagogue's Holy Ark which is the tallest in the world. Beneath ground level, the synagogue basement contains archaeological remnants of the many incarnations this synagogue has gone through.

The synagogue has become a vibrant and very popular place of Torah and Tefillah. People study there throughout the day. The prayer services in the mornings are often standing-room only.

The first rav was HaRav Simchah Kook, and after he passed away, HaRav Eliahu Zilberman became the rav.

|