"A Yid came to me," the Mashgiach of Ohrchos Torah, HaRav Chizkiyahu Mishkovsky begins, "and said to me: 'We are waiting for this period to end. The Three Weeks is not for me; it's too sad. You can't dance; you can't be joyful. We're waiting for bein hazmanim."

This is the feeling by most people. In actuality, this is a combination of several mistaken factors, leading to a situation where we are missing out on something beneficial due to lack of knowledge, understanding and thought. We fail to realize how these days are very significant and meaningful in our day-to-day living.

When we ask a Jew today why he finds it difficult to mourn, the first answer is that it is hard to mourn something that took place over two thousand years ago. "I've become accustomed to the present state of things and don't really feel that I am lacking anything."

This is similar to telling a person that his great-great-grandfather of dozens of generations back was a tycoon until at one point he lost his entire wealth. Now go and feel sorry for him.

Who at all remembers him and the huge fortune he once possessed? Who can feel remorse over that? "When you come today and tell me to mourn over what took place over two thousand years ago, I find it difficult. I don't feel any lack for it. I never even saw it."

And a second thing: No one relishes being sad. When a person is beset with sorrow, he weeps, but when everything goes well, why find something to make him cry? It's asking too much of him. "Should I be the one to cause myself anguish?"

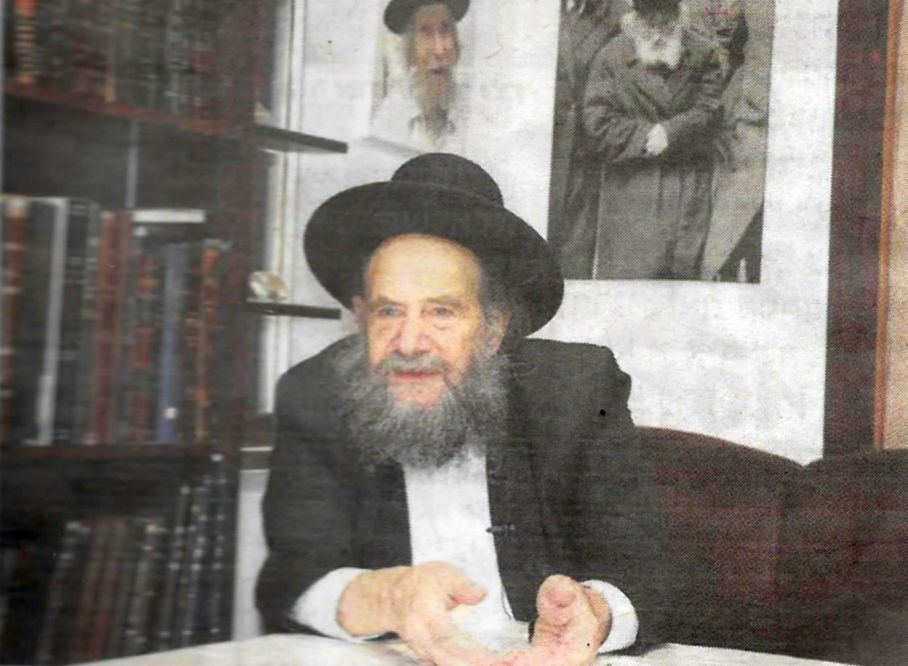

A third thing: people generally feel that to mourn over the Churban is for holy people with exalted feelings, like HaRav Yechezkel Levenstein or HaRav Eliyahu Lopian, or the late Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Aharon Leib Shteinman. "But it's not for me. I am only a simple fellow."

When all of these views combine with other opinions of the sort, one loses the whole essence and flavor of these days and fails to understand what a great treasure and opportunity they offer to enrich us so significantly.

HaRav Chaim Friedlander brings a saying attributed to HaRav Yisroel Salanter: "In the same manner that one can draw closer to Hashem through the atonement of those sins which are special to the day of Yom Kippur because it elevates a person and enables him to draw near, so, too, can one approach closer to Hashem through the avoda of this particular time, via our mourning over the Destruction of Jerusalem and the sense of the lack of the Shechina in our midst. The more a person contemplates these thoughts, internalizing them and helping them intensifying within him, this effort, too, will lead to the desire to draw closer to Hashem."

The Maharsha in Bechoros (8:1) notes that there are two series of twenty-one days: the Three Weeks of Bein Hametzarim and the twenty-one period from Rosh Hashonoh until Hoshanna Rabba. These two periods are one and the same, meaning that they each offer the chance of upgrading: that of the twenty-one day span from Rosh Hashonoh, and the similar span of twenty-one of the Three Weeks of Bein Hametzarim.

During this period, a Jew can yearn for increased spirituality and mourn his lack of it. He can build himself up and rise to a new plane of proximity to Hashem, far greater than his past level. Besides, he is also thereby helping to rebuild the Beis Hamikdash.

How, truly, can one succeed in feeling the Churban after so many years?

HaRav Mishkovsky: Precisely this year, after all of its happenings, it is all the more achievable.

Why was the first Beis Mikdash destroyed? Because of three reasons: idolatry, murder and adultery. But why was the second Temple destroyed if the people then studied Torah and kept the mitzvos? Because their existed amongst them blameless hatred. This comes to teach us that sinas chinom is tantamount to the three cardinal sins."

The three cardinal sins are very severe ones! The gemora in Nedarim and Bava Metzia says: "Who is the wise one who can understand this, and who, privy to the word of Hashem, can say why the land became lost?" Chazal asked this question but failed to answer it. The prophets also failed to supply an answer!

Until Hashem provided it Himself. Because they abandoned the Torah which I gave before them. Because they did not recite the blessing over the Torah to begin with. Rashi comments: "The fact that they did not say a blessing over the Torah reveals that they did not appreciate it as a wonderful gift."

The Ran in Nedarim writes: "...until Hashem came and revealed the answer Himself since He knows the inner thoughts of man. The Torah was not significant enough in their eyes to warrant a blessing over it. They did not study it for its own sake and therefore, made little of the need to say a blessing over it."

This seems to be an outright contradiction. Was it destroyed because of the three cardinal sins or because they failed to recite the blessing over the Torah? The Talmud Yerushalmi says, "Hashem agreed to overlook the transgressions of the three cardinal sins but refused to condone the slighting of Torah."

This caused the destruction of the land.

The Alshich tells a parable. A violinist played exceptionally beautifully. Every time the King was depressed by the pressures of running the kingdom, the violinist would come and play until he lifted up the spirits of the King so that he could carry on. One time, the violinist committed a capital crime. The King refused to sign off on the penalty. He said that he needed the services of the violinist.

Later the violinist became seriously ill and his hand was damaged and he could no longer play. When he went home, waiting for him was a red envelope informing him of his death penalty. He ran to the King. But the King said, you committed a crime for which you deserve death. I let you off because I needed you, but now that you cannot help me, you deserve death. Why should you be better than any other of my subjects?

The Alshich applies this to the history of Israel. The first Beis Hamikdash was destroyed, but as long as the violinist continued to play, meaning as long as the sweet song of Torah continued as it was supposed to be, Hashem left us alone. But when the song was no long being played as it should, when we did not learn Torah properly, then we were liable to the awful consequences of our earlier cardinal sins.

Even now, a moshol of the Netziv is very relevant. Once someone ate some badly spoiled food, but afterwards he received some unusually good-tasting food. Now, he has to vomit up the spoiled food, but if he does so he will lose also the good food.

So what does he do? He tried with all his might not to throw up so that he will not lose the good taste of the good-tasting food.

This is our situation, says the Netziv. The Land of Israel wants to vomit out all of the disgusting things that some people do in it. The Land is very repulsed by those things. But if it throws up, it will also throw up the bnei Torah. That it does not want!

So it bravely endures all the disgusting activities in order to enjoy the presence of the bnei Torah.