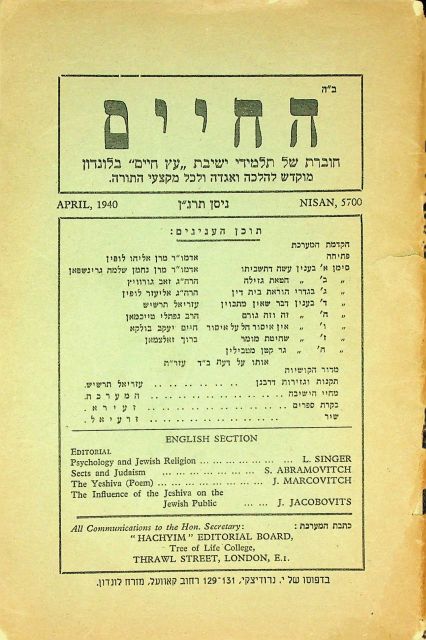

A publication of the Eitz Chaim Yeshiva in 1940

In fact, this talmid recalled, HaRav Ordman was mechadesh a great deal. However, though himself a gaon, the Rosh Yeshiva's entire attitude was that his rebbes were the source for all he understood.

Later that day, the biochemistry lecturer also announced that he had an introduction to make. He prefaced his first lecture with the arrogant order that his students forget anything they had maybe studied or previously gleaned on his topic. From now on, he said, he was going to teach them! What more eloquent demonstration could there have been of the glory of `the One who distinguishes between Yisroel and the nations'?

"In the yeshiva, schoolboys used to come in with "kushyos." They thought they were clever; they could ask a "kushya." `Rebbe,' one of them once said to him, `How do we know that the Ribono Shel Olom is emes?' [It was in the middle room in Eitz Chaim in the East End.]

"He went over to the big Shas that used to [stand] there and he almost wrapped his hands [around it and] embraced it. He said, `From the shleimus of Shas, one sees the Ribono Shel Olom.'

"[Then] he realized he was talking to schoolboys, who hadn't learned more then twenty or thirty daf. He said, `From the shleimus of the character of an odom godol you can also see the Ribono Shel Olom.' And boruch Hashem, [in the Rosh Yeshiva] we merited seeing both of those things." (From his talmid's hesped.)

During and immediately following the war, the number of bochurim in Eitz Chaim rose as refugees from Europe arrived in London. It is not hard to imagine how their plight must have moved the roshei yeshiva, who set about trying to alleviate their situation. In addition to whatever masechteh that was being learned in the yeshiva, shiurim in halacha, as well as practical guidance, were organized to train young men whose prospects for earning a living were minimal, to become sofrim or shochtim. During the sixties, a large number of Sephardic bochurim learned in the yeshiva and thanks to the training they received in Eitz Chaim, they were saved from destitution and went on to raise fine religious families of their own.

When HaRav Lopian moved to Eretz Yisroel, he entrusted HaRav Ordman with additional responsibilities in the yeshiva. In 5721, HaRav Greenspan passed away and HaRav Ordman was the obvious choice to succeed him as rosh yeshiva, a position which he occupied for the next thirty-five years.

The yeshiva's transfer in the mid sixties to North West London, where HaRav Ordman and his family had moved some time earlier, reflected the dwindling Jewish presence in the East End. Although the Golders Green neighborhood where the yeshiva is located today was then steadily developing into one of the strongest Orthodox centers in Britain, the yeshiva's enrollment remained low over the years.

While the yeshiva was presumably opened to make advanced Torah learning available to English born boys who had outgrown cheder, and who could not, or would not travel to the yeshivos in Europe, this function became largely redundant with the post war development of Gateshead in the North of England and the yeshivos in Eretz Yisroel. With the exception of a few short years in the seventies, Eitz Chaim became a yeshiva for those who, for one reason or another had to be in London.

The degree of his own institution's `success' was not seen to have any negative effect upon HaRav Ordman whatsoever, as might have been the case had his avoda been less purely inspired. He was able to sustain himself spiritually even without the stimulation of young talmidim.

His self effacement was complete. He sought neither publicity nor recognition. He continued giving his shiurim, with the same freshness and vigor as ever, irrespective of the size of his audience. The power of his delivery and the sweetness with which he conveyed the devar Hashem always remained unchanged.

One of his sons recalls that his father used to return home after delivering a shiur with sweat drenched clothes, irrespective of the season of year. Even towards the end of his life, when he was physically frail, and would begin delivering his shiur in a weak voice, his weakness quickly vanished as he grew more and more excited over the Torah he was living. The neighborhood as a whole was fortunate to host a godol beTorah whose shiurim attracted bochurim, avreichim and householders of all ages, and provided a unique opportunity to witness a level of greatness that had all but vanished.

Through the Eyes of the Bnei Hayeshiva

It was HaRav Ordman who, seeking to revive the yeshiva's spirit, asked HaRav Shmuel Rozovsky zt'l, to recommend a younger talmid chochom from Eretz Yisroel to serve alongside him as rosh yeshiva. HaRav Rozovsky's choice was HaRav Aharon Pfeuffer zt'l, a brilliant young gaon who had already earned a reputation in Eretz Yisroel as a multi-talented marbitz Torah.

HaRav Pfeuffer's arrival in Eitz Chaim heralded the beginning of a new chapter in the yeshiva's history. Together with him, a group of bochurim arrived from Eretz Yisroel, as well as some other new talmidim who had been learning in Gateshead. Several maggidei shiur also taught in the yeshiva, including HaRav Tzvi Rabi, who has succeeded HaRav Ordman as rosh yeshiva.

HaRav Pfeuffer galvanized the yeshiva and the Jews in the surrounding area with his youthful energy, sharpness of mind and beauty of character. Many new faces were attracted to the beis hamedrash. The amalgamation of several inner rooms in order to make a single, large beis hamedrash, which was undertaken at HaRav Pfeuffer's instigation, remains as a symbol of the increased importance which the yeshiva came to play in the area's religious life. HaRav Ordman greatly appreciated what HaRav Pfeuffer achieved in Eitz Chaim. Unfortunately, this period only lasted for three and a half years, as bochurim left and HaRav Pfeuffer found it increasingly difficult to stay on in London.

In the introduction to his work Sha'arei Aharon, HaRav Pfeuffer described his delight at having the opportunity to learn from HaRav Ordman. "When I was brought to England, I came to serve as a rosh yeshiva alongside the gaon HaRav Ordman. After a few days, when I realized [the extent of] his greatness in Torah, his wonderful proficiency in the entire Talmud, Bavli, Yerushalmi and midroshim, and his being a poseik in all four sections of Shulchan Oruch, [greatness] the like of which I had never seen in my life, I immediately knew in my heart that it was a great merit for me to be his talmid and I annulled myself to him and behaved towards him as a talmid to a rav. Boruch Hashem that I merited this. I learned from him ways of conducting life with mussar and a reflective approach to psak... joy to me and to my soul for HaKodosh Boruch Hu's having found me fortunate to learn from a rav who is perfect in his learning and in all his ways.'

What HaRav Pfeuffer discovered after a few days acquaintance with HaRav Ordman also became apparent to the talmidim.

In his shiurim, HaRav Ordman steered away from the abstract type of thinking which typified classical Telzer lomdus. The shiurim he developed were more basic in style. He was one of the first to apply the kind of thinking which has become popular in yeshivos. On occasion, bochurim showed him that a chidush of his appeared in Reb Elchonon's sefer, which was not published until long after HaRav Ordman had committed his own shiurim to writing.

When this happened his joy was boundless. Rather than feel in any way plagiarized, he took it as confirmation that his own thinking had been correct. He would say, `As mir geit oif glatte vegen, treft zich mit mentschen, when one follows the straight path, one meets other people.'

A talmid recalled a discussion that took place in the beis hamedrash one long Shavuos night when HaRav Ordman and the older bochurim fell to considering different approaches in learning. While more rigorous in his own approach, HaRav Ordman knew all the Rogatchover's discussions and Reb Shimon's principles that were being mentioned.

Approach to Mussar

It was in mussar that he conveyed more of the classic Telzer approach. One of his major themes was taking pride in avodas Hashem. He said that the first time he flew on an airplane, his feeling was that the higher one goes, the smaller the things below get. Similarly, the more one elevates oneself in ruchniyus, the less significant earthly concerns become.

The phrase he used to describe false pride in this worldly matters was `Geistig in Liliput' i.e. feeling like a big shot among midgets. In his weekly shiur on the parsha he might speak about the elevation experienced by the field of Efron when it passed into Jewish ownership and, in Telzer style, connect this with the mitzva of tevillas keilim. He might dwell upon the holiness inherent in human speech, citing the power of speech to effect changes in halachic status. He would sometimes examine a medrash from a number of points of view, each of which yielded a new lesson. When discussing a medrash, he would be visibly shaken, literally living the lesson which Chazal wished to convey.

His knowledge of midroshim was legendary. A bochur was once accompanying him home and they were discussing a certain medrash. HaRav Ordman invited the bochur to come into the house, so that he could show him the medrash inside. HaRav Ordman removed a sefer from the shelf, opened it and began to read. When he handed the sefer to the bochur, the latter noticed that it was not open to the correct page. (This took place shortly after HaRav Ordman had undergone eye surgery and his sight was not yet fully restored.) HaRav Ordman was most apologetic and looked for the correct page but his companion realized that he had not needed to see the page at all in order to quote the medrash word for word.

A talmid recalled his amazement at once seeing the Rosh Yeshiva take a call from one of the organizers of a large children's event who wished to know about the permissibility of engaging a magician to entertain the boys, and there and then hearing the Rosh Yeshiva quote verbatim from a Shach in Hilchos Me'onen. In fact, he had the whole of Yore Deah at his fingertips, including every Pri Megadim.

In a hesped, a local rav who knew him well recalled HaRav Ordman's reaction upon hearing of a bochur who wished to become acquainted with Yore Deah by devoting just two or three hours a week to studying it. When you learn Yore Deah, he said, you have to be involved with it twenty-four hours a day, learning nothing else. To illustrate his point, he brought out the Yore Deah which he had learned from in Telz. The volume was so worn that there was little left of it. `I ate the megilla,' was his comment.

He had an even, balanced approach in psak. He was close to the dayanim of the London batei din, who would often consult him about cases that came before them. His colleagues, the Gateshead roshei yeshiva, also occasionally referred questions to him and sheilos would arrive from rabbonim in Europe. Besides all the classic works of psak, he was thoroughly familiar with the contents of Igros Moshe, although if his own conclusion differed from that of Reb Moshe, he would say so.

It was HaRav Pfeuffer who remarked that the only person he had seen who equaled HaRav Ordman in Torah knowledge was HaRav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt'l. When HaRav Pfeuffer made a bris in the yeshiva, HaRav Ordman was sick and unable to attend. HaRav Pfeuffer went over to his mentor's tallis bag and took out the tallis. When asked what he was doing he merely responded that if his questioner truly appreciated who Reb Nosson Ordman was, he would understand.