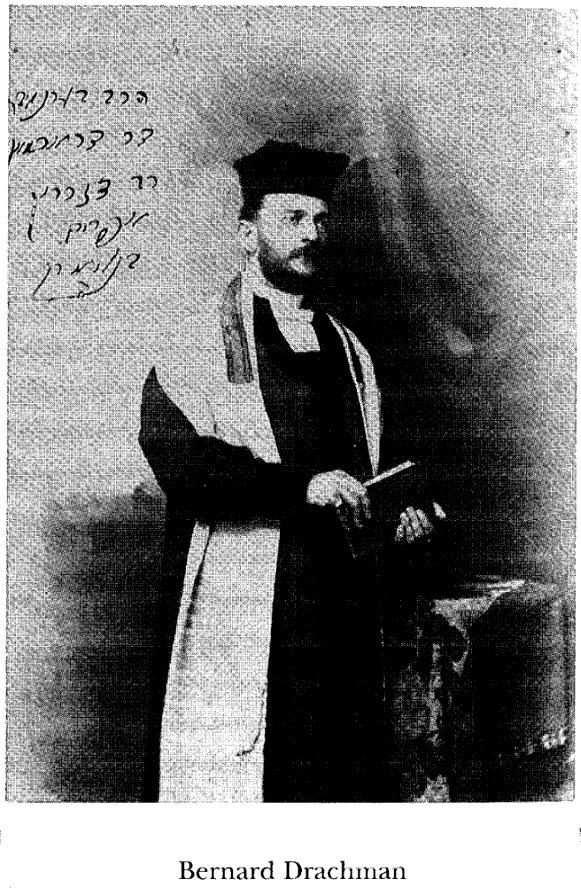

Rabbi Drachman as a young rabbi

The story of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman, who passed away over seventy-five years ago, contains important lessons for understanding about the survival of Torah in the spiritually barren and desolate land that America was a hundred years ago. Rabbi Drachman grew up in a thoroughly American environment, but he nonetheless became firmly and deeply committed to Torah true principles that were, in his person, completely at ease with his all-American heritage. Rabbi Drachman saw, with a fresh and open American eye, the flowering of HaRav Hirsch's Frankfurt, as well as the vitality of eastern Europe. He attended the funeral of Sir Moses Montefiore, officiated at the funeral of Harry Houdini and was on familiar terms with Seth Low, one of the legendary presidents of Columbia University. He also translated Hirsch's The Nineteen Letters and was responsible for Mordechai Kaplan's dismissal from his post as a rabbi in New York City in an Orthodox congregation solely because of the latter's heretical views. His fascinating story helps us understand some of the important roots of the American Jewish community.

Almost all the material in this article is based on Rabbi Drachman's autobiography The Unfailing Light.

Part I

The Man in the Context of His Times

The story of Jews in America is unique in the annals of the history of the Diaspora. In the time of the Jewish nation's first exiles, when Hashem's hashgacha was revealed, spiritual foundations were laid for nation's survival in a new environment. Before the descent to Mitzrayim, Yehuda was despatched by Yaakov Ovinu to establish a yeshiva in Goshen. The exile to Bovel after the first destruction of the was preceded by the exile of the Chorosh and the Masger, eleven years earlier, to make spiritual preparations for the nation's arrival.

Since the destruction of the Second Beis Hamikdash, the movements of the Jewish people from one country to another have been cloaked in `natural' causes, e.g. persecution in one center coincides with new opportunities elsewhere, one ruler expels his Jewish subjects and another decides to accept them and so on. In these cases, entire populations often had to move, Torah scholars and religious leaders included. The leaders then continued to guide and educate their fellow Jews in their new places of refuge. In cases when a new location was initially populated by individual Jews, mitzva observance may have been the rule but the center did not achieve prominence until Torah scholars arrived there.

With America, it was different. Some of those attracted to the new country were looking for freedom from religious persecution while others sought escape from economic discrimination and to enjoy improved material prospects. Although the newcomers did not go to America in order to lose their Jewish identity, it proved far harder to retain it in the new land of almost unlimited freedom, than it was in countries where Jews were repressed or discriminated against.

No Torah presence preceded, or even accompanied, these Jews in order to lay the spiritual foundations of religious life in the Jewish nation's new refuge. Observance, which was often weak to begin with, soon lapsed even more. There was nobody to provide instruction and, with the passage of time, ignorance took root. This situation provided fertile ground for the Reform Movement, which, in the mid-nineteenth century, became the dominant power in American Jewry.

The few individuals, both laymen and rabbonim, who were strongly committed to Orthodoxy had been raised and trained in Europe. America had no facilities for training them. Arriving in America, they battled valiantly to proclaim the truth of Torah and mitzvos but they had little effect in the vastness of America. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, when masses of Eastern European immigrants began to pour into New York harbor, America had already been viewed for a long time by European Orthodoxy as a spiritual wasteland.

It was toward the end of the nineteenth century, a few years before the mass immigrations, that Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman began his rabbinical career. The significance of his contribution to Orthodoxy in America may be somewhat overlooked by many modern observers since, at this point, attention is understandably focused on the first efforts to provide the masses of new European immigrants with spiritual guidance and instruction. Indeed, despite initial failures, that community developed several decades later, with the arrival of Torah leaders fleeing Nazi persecution, into the most spiritually dynamic segment of American Jewry, peopled by Jews who embodied the verve and energy of European Jewry, cast in American style.

Rabbi Drachman represented a different and a somewhat unique phenomenon. He was a born and bred American Jew who came to his own realization of the truth of Torah and thereafter dedicated his life to furthering the cause of Orthodoxy. He represented a synthesis of American and Jewish ideals, a synthesis that ennobled the former while brooking no compromise of the latter.

Rabbi Drachman worked during a time when the torch of Torah was still held aloft in America only by lone individuals. By the time he passed away, the torch had kindled flames in many cities and communities. Boruch Hashem, the work of countless dedicated individuals in fanning those flames during the fifty years since his passing has been blessed with success, and Torah true communities all over America now support yeshivos, kollelim and a host of other worthy institutions. Many, many Jews are blessed with the opportunity to drink from the life giving waters of Torah as much and as deeply as they can.

However, we ought not to forget that a hundred years ago, things were very different. Those who brought Torah's waters to the spiritually parched lips of Jews in those days, who were ill equipped to make their way in a world which mocked their most cherished values, deserve our recognition and respect, even if the vessels that contained their Torah were shaped somewhat differently from our own.

Early Experiences

The first few chapters of Rabbi Drachman's book deal with his childhood and early education. Were he, as a child, to have been shown a picture of the rabbi he would later become, he would probably not have known what he was looking at. (Which indeed, is probably truer of more people than we might at first think.)

His bris took place on the Fourth of July 1861, but he writes that few of his early recollections concerned things specifically Jewish. When he was almost nine, his parents moved their family from Brooklyn, New York, where they had moved a year earlier, to Jersey City in the neighboring state of New Jersey. Jersey City itself had a rural character at the time, and the Jewish community was quite small.

The children were enrolled in the local public school, where `little Bernie' or `Barney' Drachman, as he was known by his schoolfellows, received his elementary education under basically happy conditions.

Jersey City in the 19th century

While most of his schoolmates were friendly, a proportion were young Jew haters and it was in public school that he received his first taste of antisemitism. When he realized that the names yelled in his direction were meant for him, he was shocked and did not understand why he, as a Jew, deserved to be singled out for ridicule.

At home, he poured out his woes to his parents. His father assured him that Jews in no way deserved such treatment but that it was one of the tragic consequences of the golus which would continue until time of Moshiach, whose arrival had been promised by the prophets. In America, his father added, Jews had every reason to be happy and thankful to Hashem, protected as they were from the cruel persecutions that Jews were subjected to in some other countries and safe from the hatred of a few narrow minded individuals.

For a time, Bernard managed to keep his father's advice to ignore the taunts but on one occasion, he attacked an older and stronger boy who had directed one of the typical antisemitic gibes at him. After thoroughly beating first the offender and then an avenger, who could not bear to see a Jew victorious, he grew tired and was unable to continue defending himself sufficiently against a third antisemite who attacked him. He was forced to retire with slight injuries. Although technically defeated, he won general admiration for the courage and verve with which he had defended his own honor and that of his people and he never suffered again from name calling while at the school.

Bernard Drachman's father hailed from Poland. He was fluent in several languages and was well read in many fields of general knowledge. However, his greatest attachment was to Judaism although his own Hebrew education had ceased when, aged just thirteen, he had lost his own father.

One of the most powerful factors in ensuring that Bernard Drachman and his siblings did not go the way of thousands of their young coreligionists was undoubtedly their father's determination that his children should not grow up ignorant of their religious heritage. This concern prompted him to become his son's Hebrew instructor before the local Jewish community had developed enough to engage someone to fill this position. It is with pleasure that Rabbi Drachman recalls his father's lessons, during which he would translate and explain the siddur and Chumash, or expound upon the principles of Judaism or history of the Jewish people.

The suggestion that he become a rabbi was Rabbi Drachman's mother's, who was delighted when her second son expressed his preference for Jewish studies above all others. She herself was the daughter of a learned, pious and strictly observant rav, Rabbi Shemayah Stein, who had a farm near the village of Nordheim in Bavaria, a province of Southern Germany. As the daughter of yirei Shomayim and pious Jewish parents and ancestors, Mrs. Drachman possessed an unequaled respect for her Jewish heritage. While his parents' home did not conform in every way to the requirements of Orthodox Judaism, it did so in large measure and was permeated by respect for Judaism, which was far from being the case in many other so-called Jewish homes at the time. "It was only natural," says Rabbi Drachman of his parents, "that the gentle and persuasive influence of such parents, free from harshness and the stern exercise of parental authority, inspired their children with reverence for the things that were sacred to them."

During his teens, Bernard Drachman studied concurrently at the Jersey City High School and the Hebrew Preparatory School. The former was a classic American high school of that period, an institution that was not geared toward education of the masses but of an elite, and staffed by learned American scholars and gentlemen. The students were the clean-cut all-American sons and daughters of the regions' older and respected families, descendants of Dutch, English and German immigrants.

The latter institution was affiliated with the Reform Temple Emanuel of New York and its pupils received instruction in Hebrew language, Bible, Talmud and Cuzari. Most of the teachers were German rabbis and scholars whose own early Hebrew education had been traditional. While the school's stated objective was to provide its pupils with the preliminary training required for the rabbinate, rather than to inculcate Reform Judaism as such, it is clear from Rabbi Drachman's descriptions that the presentation of the material was substantially colored by the individual teachers' own views. Even at this early stage though, the young Bernard Drachman's understanding of religion was already at odds with the basic ideas of Reform Judaism.

The flowering of Rabbi Drachman's acquaintance with American culture took place during the four years he studied at Columbia College (that later developed into Columbia University). The pages in which he describes his professors, classmates and friends as well as some of the classic college experiences of those times, contain some fascinating observations on the nature of antisemitism and the relations between Jews and gentiles which reflect, as do many other episodes recounted in the book, a very different world from the one in which we live today.

Describing some firm friendships he made with gentile students, he notes these were as close as some of those he made with other Jews in later life despite the fact that it was well known in his class and in the college generally that Drachman was not only a Jew but an outspoken champion of Judaism.

Rabbi Drachman has less wholesome recollections of his two Jewish classmates' attitude to their Judaism. He writes about a questionnaire presented to the students in their senior year, one of whose sections concerned religion. While he put himself down as `Jewish,' one of the other Jewish boys simply did not answer the question while the other wrote down that he was a Unitarian!

As his course of study in Columbia neared its end, Bernard Drachman was informed by the board of directors of Emanuel Theological Seminary (which maintained the Hebrew school he had been attending) that he was to receive a stipend to enable him to pursue his rabbinical studies at one of the German institutions for training rabbis. There were three of these at the time: the Hildesheimer Rabbiner Seminar and the Hochschule fuer die Wissenschaft des Judentums, both of which were in Berlin, and the Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau.

The first of these was headed by Rav Ezriel Hildesheimer and was the most traditional in its Orthodoxy. The second owed its inception to Abraham Geiger and represented radical Reform. The third was traditional in outlook and conformed to orthodox practice, while espousing the so called `historical' view of the development of halacha (formulated by Zechariah Fraenkel, the Seminary's first director, who had passed away in 1875, and the historian Heinrich Graetz, who still taught there). The Breslau Seminary is now regarded as the ideological forerunner of the American Conservative Movement. Despite the fact that his sponsorship came from a Reform institution, Bernard Drachman was allowed to make a completely free choice as to which seminary he would attend. He knew that he definitely wanted something more traditional than Reform, and he chose the Breslau Seminary.

End of Part I

Click here for Part II